Phylogenetic relationship and geographic distribution of 580 S. aureus isolated from blood during 2019–2020

Population structure analysis of S. aureus isolated from BSIs during 2019–2020 using Bayesian hierarchical clustering of the core genome alignment showed 13 distinct sequence clusters (SCs) ranging in size from 7 to 155 genomes (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Data 1). Phylogenetic analyses revealed three dominant SCs, namely SC1, SC3, and SC8, comprising 155 (26.7% of the total population), 127 (21.9% of the total population), and 73 genomes (12.6% of the total population), respectively (Fig. 1a, pie chart 1). We performed in silico multilocus sequence typing to identify the sequence types (STs) that comprised the SC. The CCs of these STs were examined using the eBURST analysis. SC1 comprised CC1, which included ST1 (104 genomes, 67.1% of SC1), ST2725 (28 genomes, 18.1% of SC1), and ST81 (10 genomes, 6.5% of SC1) (Supplementary Data 1). SC3 comprised CC8 and, almost exclusively, ST8 (127 genomes, 84.3% of SC3). SC8 comprised CC5, which included ST5 (73 genomes, 57.5% of SC5) and ST764 (25 genomes, 34.2% of SC5). The most dominant STs of the 580 S. aureus were ST8 (18.4%), ST1 (17.9%), and ST5 (7.2%) (Fig. 1a, pie chart 2). BSI-derived S. aureus from 2019 to 2020 contained 343 isolates (59.1%) from western and 237 strains (40.9%) from eastern Japan (Fig. 1a, pie chart 3). The most dominant STs in western Japan were ST8 (23.0%), ST1 (11.9%), and ST5 (7.0%) (Fig. 1b, pie chart 1). However, the most dominant ST in eastern Japan were ST1 (26.6%), ST8 (11.8%), and ST188 (7.6%). Additionally, the major STs of CC8 were ST8 (approximately 80%) and ST630 (less than 10%) in both western and eastern Japan (Fig. 1c, middle panel). Similarly, the major STs of CC5 were ST5 (approximately 57%) and ST764 (approximately 34%) in both western and eastern Japan (Fig. 1c, right panel). A geographic comparison of the major STs in CC1 revealed significantly higher proportions of ST1 (75.9%) and ST81 (10.8%) in eastern Japan compared to in western Japan (p < 0.001 for ST1 and ST81, respectively, χ2 test), whereas ST2725 (33.3%) was more common in western Japan (p = 0.0263, χ2) (Fig. 1c, left panel). The proportion of MRSA of BSI-derived S. aureus during 2019–2020 was 46.4%, mostly SCCmecIV (76.5% of total SCCmec) (Fig. 1a, pie chart 4). The proportions of MRSA in western and eastern Japan were 47.5 and 44.7%, respectively (Fig. 1b, pie chart 2). SCCmecIV was the most common MRSA of BSI-derived S. aureus in both regions, followed by SCCmecII. The major STs of MRSA (n = 269) were ST1 (34.6%) and ST8 (26%) (Supplementary Fig. 1, left panel). In eastern Japan, the major STs of MRSA were ST1 (55.7%) and ST8 (14.2%). In addition, ST81, which belongs to CC1, was detected in eastern Japan, although in small numbers, and not in western Japan. In contrast, in western Japan, the major STs of MRSA were ST8 (33.5%) and ST1 (21.3%). The number of STs of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) was more diverse than those of MRSA (Supplementary Fig. 1, right panel). These results indicate that the representative CCs of BSI-derived S. aureus in Japan were CC1, CC8, and CC5 (Fig. 1a), with ST1 and ST2725 having different distributions in the eastern and western regions.

a Midpoint-rooted maximum-likelihood (ML) tree showing the phylogenetic structure of 580 S. aureus isolates during 2019–2020. The scale bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. Matrix shows the metadata; 1, Bayesian analysis of population structure (BAPS) sequence cluster (SC) number identified by FastBAPS; 2, Sequence type (ST) number of each S. aureus isolate; 3, indicates the eastern or western Japan where S. aureus was isolated; 4, indicates the SCCmec type of MRSA. The pie graph shows the proportion of the metadata 1–4. ST with less than 3 isolates included in other. b Genotypic distribution in eastern or western Japan. ST under top 10 included in other. c Comparison of geographic proportions of STs is shown in SC1, SC3, and SC8. The color tone is shown in the same pattern in Fig. 1. *p < 0.05; western Japan vs. eastern Japan. P-value (p) was calculated using the χ2 test. Metadata information of 580 S. aureus isolated in 2019–2020 is summarized in Supplementary Data 1.

ST764 infection is associated with high mortality

Subsequently, we investigated the association between these lineages and 30-day mortality rates. Notably, the 30-day mortality rate of S. aureus BSIs caused by the ST764-SCCmecII clone was 48% (Table 1), which was significantly higher than the 22% of the other clones (p = 0.0088, log-rank test) (Table 2). The 30-day mortality rate associated with the ST8-SCCmecI clone was also high (50%) compared to that of the other clones, although the difference was not statistically significant owing to the small sample size (n = 10). Further analysis of the ST764-SCCmecII clone revealed that age was a confounding factor significantly associated with the ST764-SCCmecII clone (p = 0.026, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test) and 30-day mortality rate (p < 0.0001, univariate Cox regression) with p-values < 0.05. The association between the ST764-SCCmecII clone and 30-day mortality rate remained significant even after controlling for the confounding effect of age (Table 2) (p = 0.04, hazard ratio 1.86, 95% CI: 1.03–3.38). There were no confounding factors in the following clinical variables: sex, diabetes, hemodialysis, surgery within 30 days before blood culture, artificial respirator use, and atopic dermatitis.

Phylogenetic relationship of BSI-derived 183 S. aureus during 1994–2000

We performed a comparative phylogenetic analysis of S. aureus isolated from BSIs during 2019–2020 and 1994–2000. We collected the BSI-derived S. aureus isolates from post-marketing surveillance conducted nationwide during 1994–2000 after levofloxacin (LVFX) was released in Japan21. Population structure analysis of 183 BSI-derived S. aureus isolated during 1994–2000 using Bayesian hierarchical clustering of the core genome alignment showed 10 distinct SCs, ranging in size from 2 to 109 genomes (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 2). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that SC-A (109 genomes, 59.6% of the total population) was dominant (Supplementary Fig. 2, pie chart 1) and comprised CC5, consisting almost exclusively of ST5 (97 genomes, 90% of SC-A, 53% of the total population). The Shannon diversity index of the STs significantly increased from 3.08399 in 1994–2000 to 4.767595 in 2019–2020. The proportion of MRSA in BSI-derived S. aureus in 1994–2000 was over 56%, mostly SCCmecII (50.8% of the total population) (Supplementary Fig. 2, pie chart 4). The proportion of STs of MRSA was almost exclusively ST5 (84.6%) (Supplementary Fig. 3, left upper panel). The most common ST of MSSA was ST5 (12.7%); however, the ST types of MSSA were more diverse than those of MRSA (Supplementary Fig. 3, right upper panel). The predominant CC of 183 S. aureus during 1994–2000 was the CC5 lineage, including the N/J clone (ST5-SCCmecII) (Supplementary Fig. 2). These results confirm the dynamic changes in the population structure of MRSA within 20 years when comparing the phylogenetic analysis data of the isolates of 1994–2000 to those of 2019–2020.

Comparative analysis of antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) pattern of BSI-derived S. aureus

We examined the differences in the number of AMR genes (ARGs) between the isolates of 2019–2020 and 1994–2000 (Supplementary Fig. 4a). The median number of ARGs was 3 in 2019–2020 and 6 in 1994–2000 (Supplementary Fig. 4a, left). For MRSA, the number of ARGs differed significantly between the two periods (median of 8 in 1994–2000 and 4 in 2019–2020; p < 2.2e-16, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test). In contrast, no significant difference was observed for MSSA, with a median of 1 in both periods (p > 0.56, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test) (Supplementary Fig. 4a, right panel). The results of the proportion of each ARG revealed that the prevalence of the aminoglycoside resistance gene aadD, tetracycline resistance gene tet(M), bleomycin resistance gene bleO, fosfomycin (FOM) resistance gene fosB, chlorhexidine resistance gene qacA decreased significantly between the two periods in the MRSA (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Conversely, the prevalence of the aminoglycoside resistance genes ant(9)-Ia, macrolide-resistant genes erm(A), erm(C), and the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) mutations (GrlA/S80F and GyrA/S84L) increased in isolates of 2019–2020 in MSSA (n = 311, p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 1). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing showed that resistance to cefazolin (CEZ), cefmetazole (CMZ), gentamicin (GM), clindamycin (CLDM), and minocycline (MINO) significantly decreased in isolates of 2019–2020 in the total samples or MRSA (p < 0.02) (Supplementary Fig. 4c, upper and middle panels). In MSSA, the level of resistance to each antibiotic was very low; however, resistance to erythromycin (EM) and LVFX increased slightly from 1994–2000 to 2019–2020 (Supplementary Fig. 4c, lower panel). We subsequently examined the distribution of ARGs in CC1, CC5, and CC8, the dominant clones of BSI-derived MRSA of 2019–2020 (Fig. 2). In CC1, the ST1-SCCmecIV and ST2725-SCCmecIV lineages contained the same number of ARGs (median: 4) (Fig. 2a, CC1) and exhibited very similar AMR patterns (Fig. 2b, C1; Supplementary Table 1; Fig. 2c, upper panel). Consistent with the presence of ARGs and QRDR mutations in ST1-SCCmecIV and ST2725-SCCmecIV, the resistance rates of these strains to oxacillin (MPIPC), EM, and LVFX were high (Fig. 2c, upper panel). In CC5, the median number of ARGs in ST5-SCCmecII was 8 in 1994–2000 and 7 in 2019–2020 (p < 0.01) (Fig. 2a, CC5). In contrast, the median number of ARGs in ST764-SCCmecII in 2019–2020 was 5, significantly lower than that in ST5-SCCmecII (median: 7; p < 0.01). In ST5-SCCmecII, blaZ, aac(6’)-aph(2”), tet(M), cat, fosB, and qacA showed decreasing trends in 2019–2020 compared to in 1994–2000 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2b, CC5; Supplementary Table 1). In ST764-SCCmecII, aac(6’)-aph(2”), tet(M), fosD, and qacB were detected at higher prevalence compared to ST5-SCCmecII (p < 0.02). Resistance rates to MPIPC, CEZ, CMZ, EM, CLDM, and LVFX remained consistently high in ST5-SCCmecII during both periods, whereas resistance rates to GM and MINO were significantly lower in 2019–2020 compared to in 1994–2000 (p < 0.01) (Fig. 2c, middle panel). In contrast, ST764-SCCmecII showed very high rates of resistance to these antibiotics, except for ABK. In CC8, the median number of ARGs in ST8-SCCmecI was 6, significantly higher than those in ST8-SCCmecIVj and ST8-SCCmecIVa, both with a median of 5 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2a, CC8). In ST8-SCCmecIVj, blaZ, ant(9)-Ia, erm(A), tet(M), and QRDR mutations (GrlA/S80F and GyrA/S84L) were prevalent, whereas aac(6’)-aph(2”) was less common (Fig. 2b, CC8 and Supplementary Table 1). ST8-SCCmecIVl showed lower proportions of ant(9)-Ia, erm(A), tet(M), and QRDR mutations (GrlA/S80F and GyrA/S84L), but higher proportions of aac(6’)-aph(2”), aadD, bleO, and qacB. Unique to ST8-SCCmecIVa, mph(C) and msr(A) were present in approximately 38% of the isolates. ST8-MRSA showed varying patterns of resistance to each antibiotic depending on the SCCmec type; however, ST8-SCCmecI was more resistant than the other clones (Fig. 2c, lower). The small number of BSI-derived USA300 isolates in Japan makes the comparative assessment difficult.

a The number of antimicrobial-resistant genes (ARGs) per strain is shown, but duplicate ARG genes are not counted. The triangle in the box indicates mean, the box indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the whiskers indicate the highest and the lowest values of the results. The line in the box indicates median. P-value (p) was calculated using the Student’s t-test. b Presence heatmap of major ARGs and quinolone resistance-determinant region (QRDR) mutations identified. The numbers in the heatmap columns are shown as percentages. *p < 0.05; ST5-II_1994-2000 vs. ST5-II_2019-2020. #p < 0.02; ST5-II_2019-2020 vs. ST764-II_2019-2020. P-value (p) was calculated using the χ2 test. c Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of BSI-derived MRSA. The radar chart shows the resistance rates of isolates to MPIPC, CEZ, CMZ, GM, ABK, EM, CLDM, MINO, and LVFX in 1994–2000 and 2019–2020.

We calculated Kendall’s concordance coefficient (W), as described in our previous study22, and we observed a certain degree of concordance between genotype and phenotype in CC1, CC5, and CC8 (Supplementary Table 2). High concordance (Kendall’s W > 0.8) was observed for EM, GM, CLDM, MINO, and LVFX, along with their corresponding resistance determinants.

Comparative analysis of virulence factor genes (VFGs) of BSI-derived S. aureus

We investigated the presence of VFGs in S. aureus isolates from BSIs. The proportion of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 gene (tst-1) decreased significantly in 2019–2020 compared to in 1994–2000 (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Additionally, the proportion of the staphylococcal enterotoxin gene cluster EGC (seg, sei, sem, sen, and seo) decreased drastically in total samples and MRSA isolates in 2019–2020 compared to in 1994–2000 (p < 0.001) but remained at approximately 30% in MSSA isolates. In contrast, the proportions of sea, seh, sek, and seq in the total samples or MRSA of 2019–2020 increased compared to 1994–2000 (p < 0.05). A few Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL) genes (lukF/S-PV), exfoliative toxin (ET) genes (eta, etb, and etd), and epidermal cell differentiation inhibitor (EDIN) genes (ednA, ednB, and ednC) were detected during both periods (Supplementary Fig. 4d). For a human-specific immune evasion cluster, the proportion of the staphylococcal complement inhibitor gene (scn) and staphylokinase gene (sak) in the two periods remained at the same level; however, that of the chemotaxis inhibitory protein Chp gene (chp) was markedly decreased in the total and MRSA.

Subsequently, we examined the distribution of VGFs in CC1, CC5, and CC8, the dominant BSI-derived MRSA in 2019–2020 (Fig. 3). In CC1, most ST1-SCCmecIV and ST2725-SCCmecIV had a high prevalence of sea, seh, sek, seq, scn, and sak, with the same distribution pattern (Fig. 3, CC1). In CC5, ST5-SCCmecII showed high proportions of sec, tst-1, EGC, and sel during both periods (Fig. 3, CC5). The proportion of seb in ST5-SCCmecII in 1994–2000 was 12% but was not detected in 2019–2020. ST764-SCCmecII exhibited high proportions of seb, seg, sei, sem, sen, and seo but lacked sec, tst-1, and sel. In CC8, sep was prevalent in ST8-SCCmecI, IVj, and IVl (Fig. 3, CC8). ST8-SCCmecIVl showed high proportions of sec, tst-1, and sel, along with additional se1 and ednA. ST8-SCCmecIVa carried sek, seq, and PVL genes (lukF/S-PV), which are characteristic of the USA300 lineage.

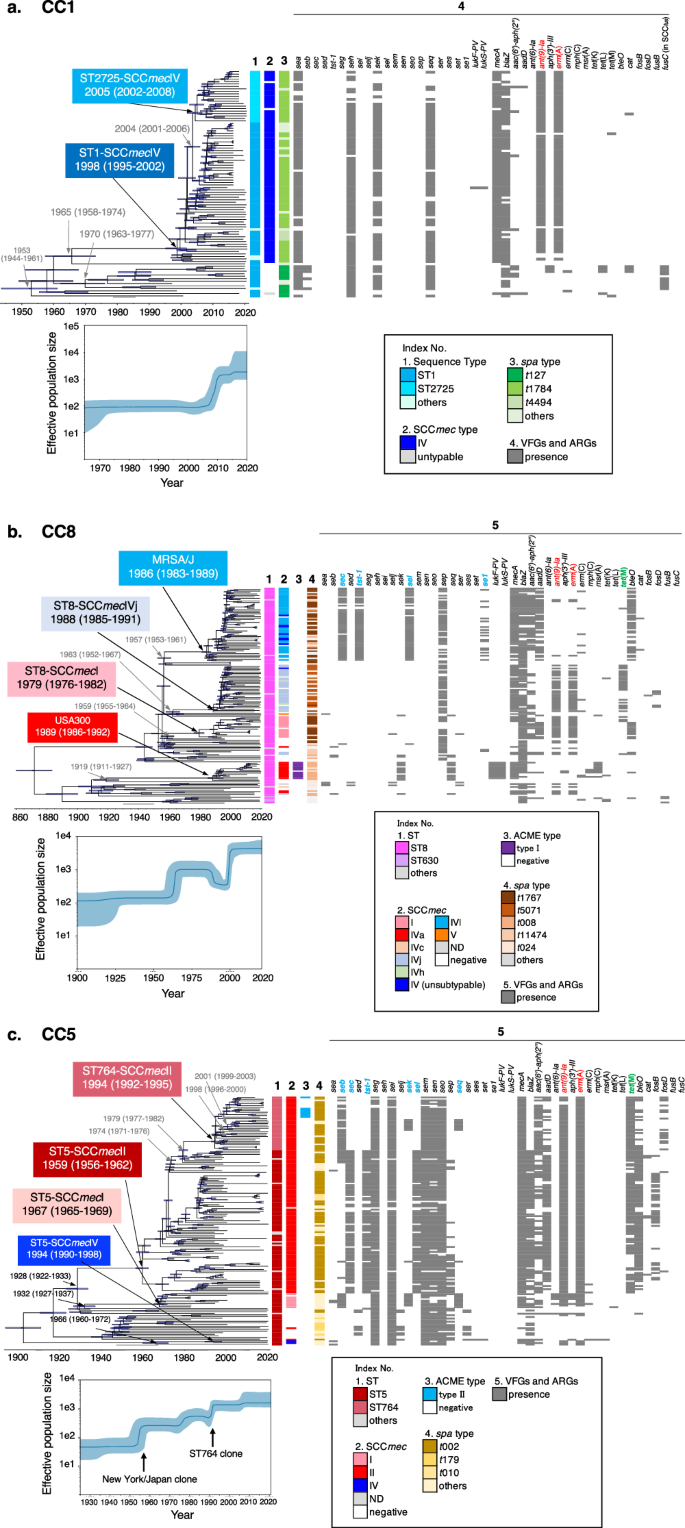

Evolutionary origins and population dynamics of three CC lineages of blood-derived S. aureus in Japan

To provide a historical perspective on the emergence of the three dominant CC lineages of S. aureus causing bacteremia in Japan, we constructed time-calibrated phylogenies of CC1 (ST1 and ST2725), CC5 (ST5 and ST764), and CC8 (MRSA/J and USA300) using Bayesian coalescent analysis implemented in the BEAST software. Each phylogenetic tree was calibrated using the isolation dates of the strains, which ranged from 1997 to 2020 (CC1) and 1982 to 2020 (CC5 and CC8), and public collection isolates with identifiable isolation dates (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 3). Root-to-tip regression analyses revealed a positive correlation between genetic distance and sampling date for each lineage (Supplementary Fig. 6). Given the presence of a temporal structure in each dataset, we performed dated coalescent phylogenetic analysis. Consequently, we estimated the time to the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of the ST1-SCCmecIV and ST2725-SCCmecIV lineages to be approximately 1998 (95% highest posterior density [HPD] intervals: 1995–2002) (Fig. 4a). The results of this analysis indicated that the ancestor of ST1-MRSA-t1784 acquired SCCmecIV, Tn554 harboring ant(9)-Ia, and erm(A)23 after 1965 (95% HPD intervals: 1958–1974). ST1-MRSA-t1784 emerged around 1998 (95% HPD intervals: 1995–2002) and started to circulate in Japan after 2000. Six years later, around 2004 (95% HPD intervals: 2001–2006), the ST2725-SCCmecIV-t1784 lineage diverged from ST1 and spread primarily to western Japan (Fig. 4a square light blue and Fig. 1c bar graph in the left panel). However, the ST1-t127 lineage diverged in 1953 and acquired the genomic island νSa4, carrying the seb and fusidic acid resistance gene fusC-harboring SCCfus24 by phage infections somewhere up to 1970. Through a timescale phylogenetic analysis, we first estimated the age of SCCfus acquisition in the ST1-t127 lineage.

The three major MRSA clones are shown in (a), CC1; (b), CC8; and (c), CC5. Upper panel indicates the Bayesian maximum clade credibility time-calibrated phylogenies based on non-recombining regions of the core genome of each CC. Arrow nodes indicate the divergence date (median estimate with 95% highest posterior). Blue horizontal bars at each node represent 95% confidence intervals. Lower panel, Bayesian skyline plots showing changes in effective population size over time. Median is represented by a dark blue line, and 95% confidence intervals are in light blue. Index No. 1–5 represents the STs, SCCmec type, ACME type, spa typing, and VFGs/AGRs, respectively. In index No. 5 of each CC, ant(9)-Ia and erm(A) harbored in Tn554 are indicated in red. In CC8 (b), MRSA/J acquired SCCmecIVl, genomic island vSa4, and se1-harboring plasmid somewhere between 1957 and 1986. sec, tst-1, and sel on vSa4 and se1-harboring plasmid are indicated in blue (see also Supplementary Fig. 7a and b). Some strains of ST8-SCCmecIVj and ST8-SCCmecI acquired tet(M)-harboring Tn916-like transposable unit somewhere between the late 1980s and 1990s. tet(M) is indicated in green (see also Supplementary Fig. 7c). In CC5 (c), in the process leading to the emergence of ST5-SCCmecII (N/J clone) and ST764-SCCmecII, it is estimated that SCCmecII, genomic islands, and transposons were acquired stepwise. The related VFGs are indicated in blue, and tet(M) is indicated in green (see also Supplementary Fig. 8).

In CC8, USA300 isolated from BSIs in Japan belonged to the USA300-NAE (North American Epidemic) lineage25 and appeared around 1989 (95% HPD intervals: 1986–1992) (Fig. 4b). This is consistent with the previously reported data25. The trajectory of the emergence of ST8-SCCmecIVl (MRSA/J) (Fig. 4b, square light blue) was somewhere between 1957 and 1986, when it acquired SCCmecIVl and νSa4 (carrying sec, tst-1, and sel) by phage infections (Fig. 4b, light blue of index No. 2 and 5, and Supplementary Fig. 7a) and plasmids carrying se1 (Fig. 4b, light blue of index No. 5, and Supplementary Fig. 7b), emerging around 1986 (95% HPD intervals: 1983–1989) contemporaneously and in parallel with the USA300-NAE lineage (SCCmec IVa-arginine catabolic mobile element [ACME] type I). In addition, the ST8-SCCmecI and ST8-SCCmecIVj lineages emerged around 1979 (95% HPD interval: 1976–1982) and 1988 (95% HPD interval: 1985–1991), respectively. Some strains of the ST8-SCCmecI and ST8-SCCmecIVj lineages were estimated to have acquired tet(M)-harboring Tn916-like transposable units in the late 1980s and 1990s (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 7c). These multiple ST8 lineages emerged one after another during the 1980s–1990s, and the effective population size of CC8 increased in the late 1990s–2000s (Fig. 4b, lower).

In CC5, we estimated the tMRCA of the ST5-SCCmecII (N/J clone) and ST764-SCCmecII lineages to be around 1959 (95% HPD interval: 1956–1962) (Fig. 4c). Our genome sequence comparison inferred the trajectory of the emergence of the ST764-SCCmecII clone from the N/J clone based on recombination events (index No. 5 in Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 8). At the first step, somewhere between 1928 and 1959, SCCmecII, genomic island νSa3 (carrying sec, tst-1, and sel) (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 8a) and tet(M)-harboring Tn916-like transposable unit (Supplementary Fig. 8b) were acquired by phage infection or transposition, respectively, resulting in the emergence of ST5-SCCmecII (N/J clone). In the second step, after 1974 (95% HPD interval: 1971–1976), N/J clones acquired the genomic island νSa4 carrying seb by phage infection and emerged as a seb-positive-N/J lineage, which evolved into the ST764-SCCmecII lineage (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 8c). At the third step, genomic island νSa3 (carrying sec, tst-1, and sel) was replaced by a completely different phage, followed by a recombination event at the same location at the νSa3 of N/J clone, loosing blaZ (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 8a). Finally, approximately 20 years after the emergence of the N/J clone, around 1979 (95% HPD intervals: 1977–1982), the ST764-SCCmecII lineage diverged from ST5 and spread throughout Japan after 1994. One sub-lineage of ST764-SCCmecII acquired the genomic island νSa1 carrying sek and seq by phage infection somewhere between 1998–2001 (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 8d). Another ST764-SCCmecII sub-lineage acquired ACME type II somewhere between 1996 and 1999 (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 8e). However, the ST5-SCCmecI ancestor diverged from the N/J lineage around 1928, and somewhere between 1932–1967, the ST5-SCCmecI lineage emerged by acquiring SCCmecI and νSa4 (carrying sec, sek, and seq) by phage infections but did not spread as far in Japan (Supplementary Data 1 and 2). ST5-SCCmecIV followed a different phylogenetic trajectory from the clones described above, emerging somewhere between 1966 and 1994 with the acquisition of SCCmecI, which was also not widespread in Japan (Fig. 4c). The effective population size of CC5 increased in a staircase-like manner during the emergence of ST5-SCCmecII and ST764-SCCmecII (Fig. 4c, lower panel).