Assessment of EAT efficacy in patients with long COVID

All patients underwent EAT once a week over a 3-month period. We utilized two main parameters to assess treatment effectiveness: the inflammation score of chronic epipharyngitis and the VAS score for the primary complaint. The endoscopic findings of the epipharynx at the initial visit (pre-EAT) and 3 months after the commencement of EAT (post-EAT) are shown in Fig. 1a, which represents the results for Patient 2. Supplementary Video 1 shows the endoscopic findings of the epipharynx at the initial visit (pre-EAT) during EAT, and Supplementary Video 2 shows the findings 3 months after the commencement of EAT (post-EAT) for Patient 2.

Assessment of Epipharyngeal Abrasive Therapy (EAT) on Macroscopic Epipharyngeal Inflammation and Viral mRNA Expression in Long COVID Patients. (a) EAT alleviated the macroscopic epipharyngeal inflammation in long COVID patients. These panels show the endoscopic characteristics in both standard light and narrow-band imaging (NBI) modes and drainage induced by EAT. The left panels show the endoscopic characteristics at the first visit. The right panels show the endoscopic characteristics 3 months after EAT. The white arrowhead indicates swelling of the epipharyngeal mucosa, the white arrow indicates mucus and crust adhesion, and the black arrow indicates a sterile nasal cotton swab containing zinc chloride. (b) Expression patterns of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA in the epipharynx in patients with long COVID before and after epipharyngeal abrasive therapy (EAT). The left panels show the staining results of the epipharyngeal tissues before and after EAT in Patients 1 to 3. The right panels show the staining results of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike FFPE 293 T cell pellet slide (GTX435744) as the positive control, and the staining results of epipharyngeal tissue from a patient with chronic epipharyngitis prior to the COVID-19 outbreak as the negative control. Brown dots represent SARS-CoV-2 mRNA. Scale bar, 100 μm.

The findings for Patients 1 and 3 are presented in Supplementary Fig. S2. The details of these scores, both pre- and post-EAT, are presented in Table 1. Following EAT, all patients showed significant improvement in their symptoms. The inflammation scores for these patients considerably decreased, and their VAS scores indicated that their primary complaints were alleviated to a point where they no longer faced hindrances in their daily lives.

EAT reduced the levels of residual SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the epipharynx

At the initial consultation, the presence of residual SARS-CoV-2 spike RNA in the epipharynx was confirmed in all three patients, each with varying infection timelines, via in situ hybridization (Fig. 1b). After the administration of EAT once a week for 3 months, the expression of viral RNA disappeared in patients 1 and 2. Patient 3 presented a substantial reduction in viral RNA expression; although complete clearance was not achieved, a marked decrease was observed.

Spatial gene expression analysis of the epipharynx in long COVID

Spatial transcriptomics analysis was performed using the high-resolution Visium HD Spatial Gene Expression platform (10 × Genomics, Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA), and the results for Patient 2 before EAT are shown in Fig. 2a. Cluster analysis was conducted to elucidate gene expression patterns in the epipharynx. Using the Seurat package, dimensionality reduction was performed with UMAP for cluster visualization. The analysis identified 16 distinct clusters derived from seven samples: two samples from noninfected individuals, three samples from long COVID patients, and two samples from three long COVID patients post-EAT (Fig. 2b and c). Each cluster was categorized on the basis of gene expression profiles, reflecting different biological characteristics of the epipharynx. The top 5 DEGs for each cluster are presented in the form of a heatmap (Fig. 2d). DEGs other than the top 5 for each cluster are provided in Supplementary File 1. Spatial gene expression analysis was employed to highlight the distribution of cell clusters within the tissue, revealing two major groups of cells on the basis of their spatial distribution: epithelial cells and nonepithelial cells. The epithelial clusters included Clusters 6, 7, 9, 4, 12, and 13. These cells are predominantly composed of nonhaematopoietic cell populations, such as epithelial cells, ciliated cells, and squamous epithelial cells, and are distributed mainly in the epithelial layer. Clusters 6 and 7 presented high expression of genes such as TPPP3, RSPH1, and FOXJ1, indicating a population of ciliated epithelial cells. Clusters 12 and 9 were observed specifically in post-EAT samples, suggesting their involvement in epithelial remodelling and repair processes following therapy. Cluster 4 displayed high expression of basal cell markers such as KRT5, KRT14, and TP63, as well as genes such as COL17A1, LAMA3, and EGFR, indicating that basal cells are involved in regeneration and differentiation. Cluster 13 was characterized by high expression of inflammation-related genes such as LTF and CCL20, suggesting that a cell population is involved in the immune response. The nonepithelial clusters included Clusters 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 10, 11, 14, and 15 and were primarily composed of immune cells, endothelial cells, dendritic cells, and stromal cells. Cluster 0 presented high expression of genes related to plasma cells, indicating a population of antibody-secreting cells. Cluster 2 was characterized by high expression of B-cell-specific markers, suggesting a population of B cells. Cluster 1 displayed high expression of T-cell-related genes, as well as macrophage-related genes, indicating a mixed population of T cells and macrophages. Cluster 3 exhibited high expression of VWF and other endothelial cell-specific genes, indicating vascular endothelial cells. Cluster 5, which lacked distinctive gene expression patterns, suggested a mixed population of various immune cells and supporting cells. Cluster 8 exhibited high expression of collagen-related genes, indicating fibroblasts. Cluster 10 demonstrated high expression of CPA3 (a mast cell marker) and CTSG (a neutrophil marker), suggesting the presence of mast cells and neutrophils. Cluster 11 displayed high expression of ACTA2 and other smooth muscle-specific genes, suggesting smooth muscle cells. Cluster 14 was characterized by high expression of PROX1, a marker of lymphatic endothelial cells, whereas Cluster 15 was characterized by high expression of genes characteristic of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs).

Clustering and gene expression analysis of epipharyngeal cells in control and long COVID samples. (a) The left panel shows H&E staining of the epipharyngeal tissue, whereas the right panel displays a clustering map generated via Visium HD on the same region. The upper panels present a low-magnification view, with the dotted box indicating the area that is further magnified in the lower panels. This highlights the high resolution of Visium HD, which enables gene expression analysis at a near single-cell scale. The Visium HD platform achieves a resolution of 8 µm per bin, allowing detailed mapping of gene expression patterns within the complex structure of the epipharyngeal tissue. The black arrow indicates the epithelial region, the white arrowhead indicates the basement membrane, the white double-headed arrow indicates the submucosal region rich in immune cells, and the black arrowhead indicates a blood vessel. This capability facilitates the distinction between epithelial and subepithelial regions and enables comparative analysis of various immune cell populations present in the epipharynx. The cells from the epipharyngeal sample were classified into 16 clusters and mapped onto the tissue. (b) Cells from epipharyngeal samples, including control (n = 2), long COVID pre-EAT (n = 3), and long COVID post-EAT (n = 2) samples, were classified into 16 clusters and mapped onto the tissue. (c) The 16 clusters are visualized via a UMAP plot with dimension reduction. Each cluster was classified into epithelial clusters and nonepithelial clusters on the basis of their distribution within the tissue. (d) Heatmap showing the top 5 DEGs for each of the 16 clusters in the epipharynx.

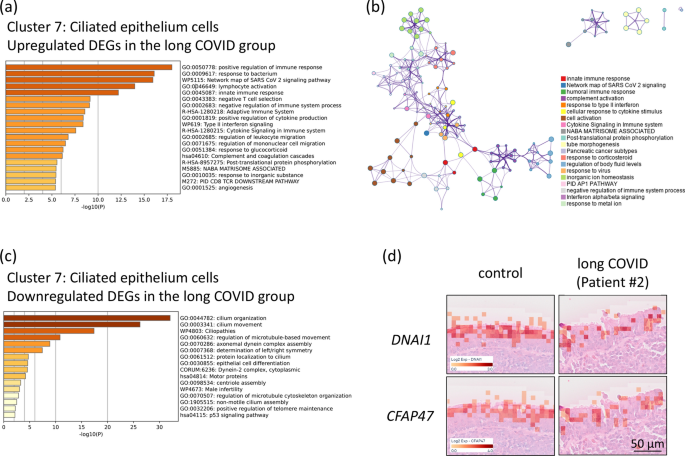

Activation of the SARS-CoV-2 signalling pathway and impairment of ciliary function in the epipharyngeal epithelium in patients with long COVID

A comparative gene expression analysis was conducted on the epipharyngeal epithelium (Cluster 7) of three patients with long COVID and two control individuals without COVID-19 to identify DEGs. Gene ontology and pathway enrichment analysis via Metascape revealed that the network map of SARS-CoV-2 signalling (WP5115) was activated in the epipharyngeal epithelia of patients with long COVID (Fig. 3a). This finding suggests the possibility of persistent viral activity in the epipharyngeal tissue, potentially contributing to prolonged symptoms and inflammatory responses associated with long COVID. Furthermore, the network map of SARS-CoV-2 signalling was interconnected with other key immune pathways, including cytokine signalling in the immune system (R-HSA-1280215) and response to virus (GO:0,009,615) (Fig. 3b). These interconnected networks suggest that the persistent immune activation observed in the epipharynxes of patients with long COVID may be initiated by SARS-CoV-2 as the trigger of broader immune responses, contributing to chronic inflammation and prolonged symptoms. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces inflammation and leads to ciliary dysfunction and abnormal ciliary activity21. Consistently, there was a decline in pathways related to cilium organization (GO:0,044,782) and cilium movement (GO:0,003,341) in the epipharyngeal epithelium (Fig. 3c). Histological analysis via H&E staining also confirmed ciliary structural damage in the epipharynx in the long COVID group, with significantly lower expression of Dynein Axonemal Intermediate Chain 1 (DNAI1) (adjusted p = 9.73E-61) and Cilia and Flagella Associated Protein 47 (CFAP47) (adjusted p = 7.23E-49) than in the control group, both of which are involved in ciliary function (Fig. 3d). These results suggest that long-term functional impairment of the epipharyngeal epithelium persists in patients with long COVID. The observed dysregulation of immune and ciliary pathways highlights the complex pathophysiology of long-term COVID, potentially contributing to the persistence of symptoms in affected individuals.

Differential Gene Expression of Epithelial Cell Clusters in the Epipharynx between the Control and Long COVID Groups. (a) Bar graph of the enriched GO terms in the upregulated DEGs in epipharyngeal epithelial cells (Cluster 7) of the long COVID group compared with the control group. (b) Network of the enriched terms in the upregulated DEGs in the epipharyngeal epithelial cells (Cluster 7) of the long COVID group compared with the control group. The top 20 clusters were selected and rendered as a network, in which terms with a similarity score > 0.3 are connected by an edge. The thickness of the edge represents the similarity score. (c) Bar graph of the enriched terms in the downregulated DEGs in the epipharyngeal epithelium cells (Cluster 7) of the long COVID group compared with the control group. (d) Spatial gene expression analysis was used to map the expression levels of the Dynein Axonemal Intermediate Chain 1 (DNAI1) and Cilia and Flagella-Associated Protein 47 (CFAP47) genes onto the epipharyngeal tissue in both the control group and the long COVID group. Scale bar, 50 µm.

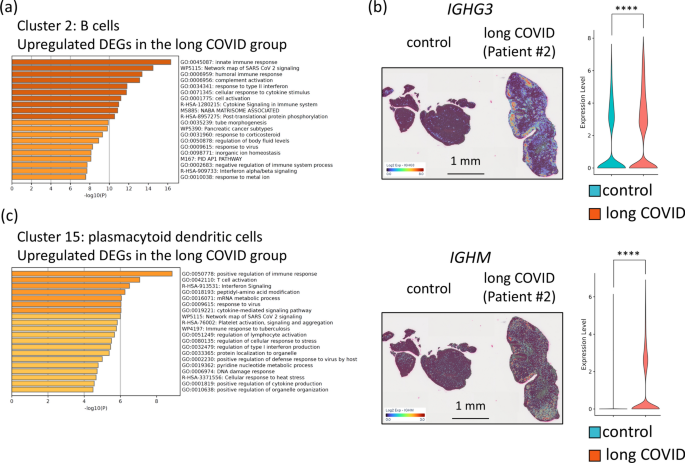

Increased activation of SARS-CoV-2-related pathways in immune cells in the epipharynx in patients with long COVID

Gene expression analysis of B cells (Cluster 2) from patients with long COVID revealed activation of the network map of SARS-CoV-2 signalling (WP5115). This activation suggests a sustained immune response against residual viral antigens in patients with long COVID. In addition, pathways related to cell activation (GO:0,001,775) and positive regulation of the immune response (GO:0,050,778) were also enriched in the upregulated DEGs in B cells, indicating an enhanced immune response (Fig. 4a). This heightened activity in B cells may lead to the activation and differentiation of plasma cells. Indeed, gene expression analysis of the plasma cell cluster (Cluster 0) revealed significantly higher expression levels of IGHG3 and IGHM in patients with long COVID than in the control group (Fig. 4b). These findings imply persistent immune activation and chronic inflammatory responses in patients with long COVID. Moreover, in the plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) (Cluster 15) of patients with long COVID, several pathways, including positive regulation of the immune response (GO:0,050,778) and interferon signalling (R-HSA-913531), were significantly enriched. Pathways related to the response to viruses (GO:0,009,615) and the network map of SARS-CoV-2 signalling (WP5115) were also enriched (Fig. 4c). These findings suggest that pDCs continue to recognize and respond to viral components, triggering excessive immune responses and maintaining a chronic inflammatory state in the upper pharynxes of patients with long COVID. The activation of these pathways in pDCs, together with the heightened responses of B cells and plasma cells, indicates that a complex network of interactions contributes to prolonged inflammation and immune dysregulation in patients with long COVID. Although no significant pathways (q < 0.01) were detected in T cells (Cluster 1), several immune-related pathways were enriched, including the regulation of the MAPK cascade (GO:0,043,408) and the binding of TNFs to their physiological receptors (R-HSA-5669034) (Supplementary Fig. S3). These findings suggest that T cells still play a subtle role in the immune dysregulation observed in patients with long COVID. Collectively, these findings indicate that interactions among pDCs, B cells, plasma cells, and T cells contribute to the chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation characteristic of patients with long COVID, highlighting the complex and multifaceted nature of the immune response in this condition.

Differential gene expression in the immune cell clusters in the epipharynx between the control and long COVID groups. (a) Bar graph of the enriched terms in the upregulated DEGs in the B cells (Cluster 2) of the long COVID group compared with the control group. (b) Changes in IGHG3 and IGHM gene expression in the epipharynx between the control and long COVID groups. The left panels show spatial gene expression analysis mapping the expression levels of the IGHG3 and IGHM genes onto the epipharyngeal tissue. The right panels show violin plots depicting the expression levels of these two genes. Blue represents data from the control group, whereas red indicates data from the long COVID group. ***p < 0.0001. (c) Bar graph of the enriched terms in the upregulated DEGs in the plasmacytoid dendritic cells (cluster 15) of the long COVID group compared with the control group.

Epipharyngeal abrasive therapy (EAT) eliminates infection-induced dysfunctional ciliated epithelium in long COVID patients

In the pre-EAT state of long COVID Patient 2, the tissue surface was predominantly covered by ciliated epithelium (Cluster 7). In contrast, following treatment, the ciliated epithelium was no longer observed, and a new cluster of squamous epithelial cells (Cluster 12) emerged, which was confirmed by histological analysis (Fig. 5a). Enrichment analysis of the newly emerged cluster (Cluster 12 in Patients 2 and 9 in Patient 1), which appeared on the apical surface, was performed using the top 300 DEGs and revealed the activation of pathways associated with the squamous epithelium, including epidermis development (GO:0,008,544), differentiation of keratinocytes in the interfollicular epidermis in the establishment of the skin barrier (GO:0,061,436) and formation of the cornified envelope (R-HSA-6809371) (Fig. 5b). These findings suggest that squamous metaplasia occurred at the genetic level. Collectively, these results demonstrate that EAT effectively eliminates the inflamed ciliated epithelium in patients with long COVID and induces the formation of squamous cells with high barrier function.

Spatial gene expression and histological analysis of the epipharyngeal epithelium before and after treatment in patients with long COVID. (a) The upper panels show the spatial gene expression analysis of the epipharyngeal tissue in long COVID patients pre-EAT and post-EAT. The epithelium pre-EAT showed a higher proportion of Cluster 7, whereas the epithelium post-EAT showed higher proportions of Clusters 12 and 9, each of which is highlighted in yellow in the tissue. The lower panels display H&E staining results with magnified views of the epithelium, highlighting structural changes before and after treatment. (b) Bar graph of the enriched terms in the upregulated DEGs in Clusters 12 and 9, representing the post-EAT epithelium.

Modulation of T-cell receptor pathways, inflammatory cytokines, and IGHM expression in the epipharynxes of patients with long COVID-via EAT

EAT was found to suppress both T-cell receptor (TCR)-related pathways and downregulate inflammatory cytokine expression in the epipharynxes of long COVID patients. Analysis of the “Network Map of SARS-CoV-2 (WP5115)” revealed that the activation of TCR signalling cascades (TCR signalling kinases and TCR subunits) in the T-cell population of Cluster 1 was inhibited following EAT (Fig. 6a). IL-6, which is known to promote the proliferation of T cells, and TNF-α, which is released from T cells to exert antiviral effects, were both downregulated after EAT. Spatial gene expression analysis revealed a decrease in the expression of inflammation-related cytokines in both Patient 1 and Patient 2 after treatment. Patient 2’s results are shown as a representative in Fig. 6b, whereas the results for Patient 1 are presented in Supplementary Fig. S4. Furthermore, all patients showed a reduction in the expression of IL-6 and TNFα in situ after EAT (Fig. 6c). Spatial gene expression analysis revealed a decrease in the expression of IGHM after treatment in Patients 1 and 2 (Fig. 6d). Indeed, gene expression analysis of the plasma cell cluster (Cluster 0) revealed significantly lower expression levels of IGHM in the long COVID post-EAT group than in the long COVID pre-EAT group (p < 0.001). These findings suggest that EAT may effectively reduce excessive activation of TCR-related pathways, persistent inflammation, and overactivation of humoral immune responses in the epipharynx, potentially contributing to the clinical improvements observed in patients with long COVID.

Changes in TCR Signalling, Inflammatory Cytokine Expression, and IGHM Gene Expression in Long COVID Patients Pre- and Post-EAT. (a) Comparison of T-cell receptor (TCR) signalling kinase and TCR subunit expression levels in cluster 1 between the long COVID pre-EAT group and the post-EAT group. The panels show violin plots depicting the scores calculated on the basis of the expression levels of TCR signalling kinases and TCR subunits from the network map of SARS-CoV-2. Red represents long COVID pre-EAT and blue represents long COVID post-EAT. ***p < 0.001. ****p < 0.0001. (b) Spatial gene expression analysis was used to map the expression levels of the IL-6 and TNF genes onto the epipharyngeal tissue in both pre-EAT and post-EAT samples, highlighting the spatial distribution of these inflammatory markers. Scale bar, 1 mm. (c) These panels depict the mRNA expression patterns of IL-6 and TNF-α in the subepithelial region of the epipharyngeal tissues from patients with long COVID as determined by in situ hybridization. Each row represents a different patient (Patients 1 to 3), with the left and right panels showing IL-6 and TNF-α expression, respectively. The top row of images shows the expression pre-EAT, whereas the bottom row shows the expression post-EAT. The brown dots represent IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA. Scale bar, 25 μm. (d) Spatial gene expression analysis maps the expression levels of IGHM genes onto the epipharyngeal tissue in both pre-EAT and post-EAT samples, highlighting the spatial distribution of IGHM. Scale bar, 1 mm.