To identify the factors influencing the energy deposited by a single photon in the high-carbon steel irradiated sample and to optimize the irradiation device parameters for improving the sterilization efficiency of medical surgical blades, we employed the MCNP software using the Monte Carlo simulation method. Through this approach, we established a model for irradiating medical surgical blades and simulated various relevant parameters. The results indicate that the factors affecting gamma photon energy deposited in the high-carbon steel irradiated sample include the energy of the gamma photons emitted by the radiation source, the thickness of the radiation source, the material and thickness of the reflector, the shape of the reflector, the source-to-sample distance, and the size of the high-carbon steel sample. Since the gamma photons emitted by the radiation source predominantly penetrate the high-carbon steel sample from the top down, the energy deposited by a single photon in the lower sample layers is less than that in the upper layers. We use the energy deposited in the bottom layer as the vital research index to ensure the complete sterilization of the high-carbon steel sample by gamma rays. We set the number of particle histories in each simulation to 109 to ensure that the error in each result does not exceed 0.001.

The effect of the radiation source on the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel irradiated sample

The effect of source photon energy on the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel irradiated sample

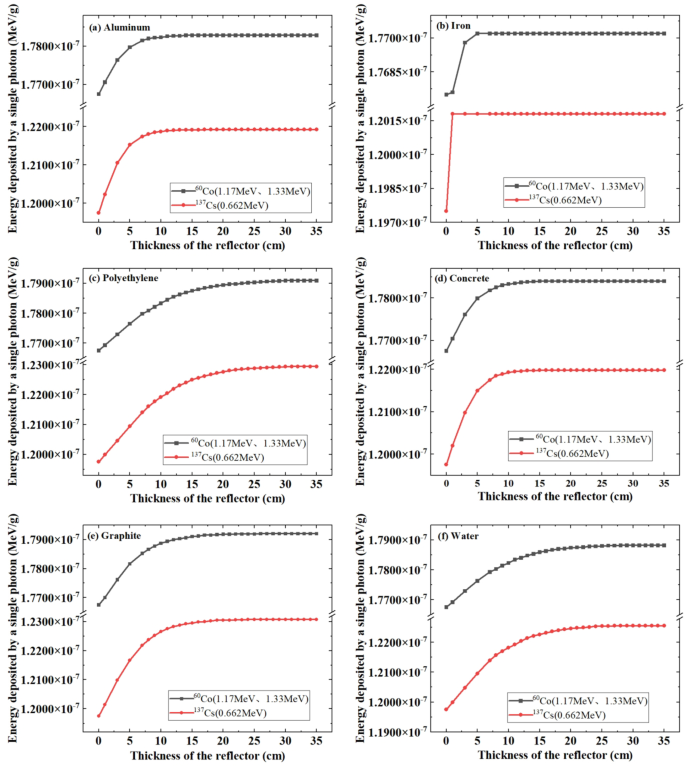

Figure 4 illustrates the scenario where the reflector is a cubic shell, the source-to-sample distance is 90 cm, the sample size corresponds to group A and the thickness of the radiation source is set to 2 cm. The radiation sources used are 60Co, emitting one gamma photon of 1.17 MeV and 1.33 MeV per decay, and 137Cs, emitting one gamma photon of 0.662 MeV per decay. The reflector materials are aluminum, iron, polyethylene, concrete, graphite, and water.

The findings suggest that the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the irradiated sample varies depending on the reflector’s thickness. It is evident that as the reflector thickness increases to a certain point, the energy deposited in the bottom layer stabilizes and no longer changes. Additionally, gamma photons with energies of 1.17 MeV and 1.33 MeV (i.e., those produced by the decay of 60Co) deposit more energy in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel sample than the photons from 137Cs.

This result occurs because most photons generated by the radiation source interact directly with the high-carbon steel sample once they pass through the air. Photons with higher energy retain more energy after interacting with the air, meaning that the photons that reach the sample layer have tremendous energy, allowing them to deposit more energy into the sample. Another portion of the photons does not interact directly with the sample but instead interacts with the reflector, where they are scattered. Some of these scattered photons are reflected toward the high-carbon steel sample. The higher-energy source photons retain more energy after traversing the same air and interacting with the reflector, thereby deposing more energy into the high-carbon steel sample.

Based on this, we use 60Co as the radiation source in the subsequent stages of the study due to its higher energy deposition efficiency.

The effect of the thickness of the radiation source on the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel irradiated sample

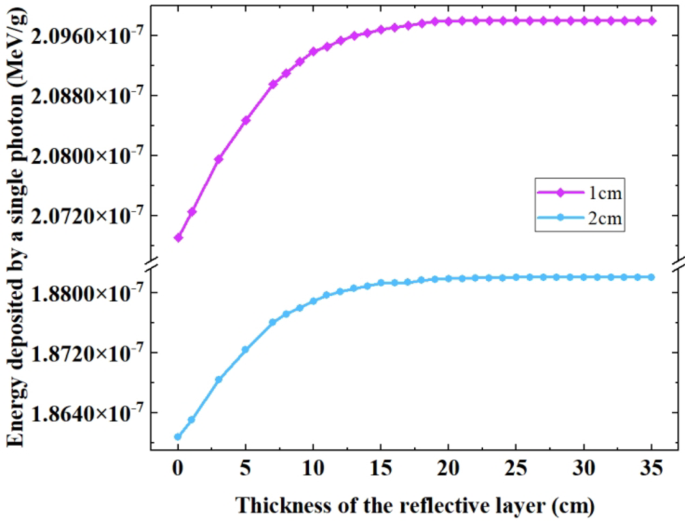

Figure 5 presents the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel sample when the reflector is a cylindrical shell made of graphite, the source-to-sample distance is 90 cm, and the size of the irradiated sample is group A. The radiation source used is 60Co, with gamma radiation source thicknesses of 1 cm and 2 cm, respectively.

The results show that when the radiation source area is the same, the single photon released from the thinner source deposits more energy in the bottom sample layer. Two factors can explain this outcome. First, photons released from the radiation source interact with the atoms of the source material itself, causing them to lose energy. Consequently, the average energy of the gamma photons emitted from a thicker radiation source is lower when they reach the high-carbon steel sample, leading to reduced energy deposition. Second, photons emitted upwards from the source interact with the reflector and then pass through the radiation source again before reaching the high-carbon steel sample. A thicker radiation source causes the reflected photons to lose more energy before interacting with the sample. Thus, in practical applications, when the type and activity of the radiation source are the same, a radiation source with a smaller thickness should be chosen, as this effectively results in a higher energy deposition, improving the sterilization process, also referred to as a single-grid source or a grid source composed of finer source pencils.

The effect of the reflector on the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel irradiated sample

The effect of the reflector material and thickness on energy deposited by a single photon

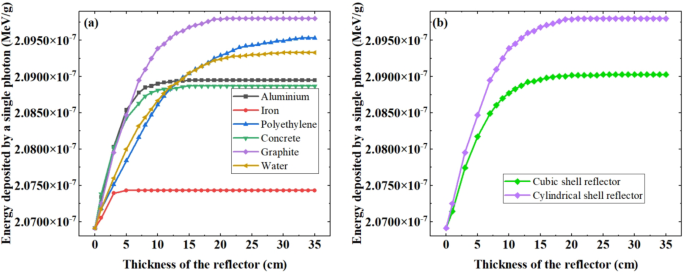

Figure 6 (a) shows the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel sample when the reflector is in the shape of a cylindrical shell. In this setup, the source-to-sample distance is 90 cm, the sample size is group A, the radiation source is a 60Co source with a thickness of 1 cm, and the reflector materials are aluminum, iron, polyethylene, concrete, graphite, and water. The results indicate that as the thickness of the reflector increases, the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel sample also gradually increases, eventually reaching a stable value. At this point, the energy deposition ranks from highest to lowest: graphite, polyethylene, water, concrete, aluminum, and iron. The thickness required for stabilization varies for each material, with the values being 20 cm for graphite, 30 cm for polyethylene, 28 cm for water, 15 cm for concrete, 15 cm for aluminum, and 5 cm for iron. These findings align with those reported in the studies by Arvind D. Sabharwal34 and Ying-Hong Zuo35.

These results arise from the fact that when gamma photons with energies of 1.17 MeV and 1.33 MeV are released from the radiation source, a portion of these photons interact directly with the high-carbon steel sample and deposits energy after traversing the air. Additionally, a small fraction of these photons undergoes scattering in the high-carbon steel sample, either continuing to penetrate or exiting the sample layer. After passing through the air, another portion of the photons first interacts with the reflector, producing a photoelectric effect or Compton scattering. Some of these scattered photons then interact with the high-carbon steel sample, depositing energy through the photoelectric effect or further scattering within the sample layer before continuing to penetrate or exit. When gamma photons interact with a reflector made of materials with low atomic numbers, such as graphite, polyethylene, and water, Compton scattering is more likely to occur. This results in more photons interacting with the high-carbon steel sample after being scattered by the reflector, increasing the total energy deposited in the high-carbon steel sample. Once the reflector reaches a specific thickness, photons can no longer penetrate it, and the count of scattered photons interacting with the sample stabilizes, as does the total energy deposited.

Specifically, polyethylene, with its small atomic number and low density (0.93 g/cm³), is less likely to interact with gamma photons. As a result, the thickness of the polyethylene reflector must be twice that of aluminum to achieve the same stable energy deposition per photon. In contrast, when gamma photons interact with high atomic number materials like iron, the probability of Compton scattering decreases, and the photoelectric effect dominates. In this process, the gamma photons transfer their energy to the iron atoms, ejecting photoelectrons. These photoelectrons gradually lose energy through interactions with the iron reflector or the surrounding air, eventually being absorbed. Graphite has a relatively low atomic number, which primarily causes gamma photons interacting with it to undergo Compton scattering. However, its high density increases the likelihood of interactions with photons, allowing it to increase the number of scattered photons interacting with the high-carbon steel sample while maintaining a smaller stable thickness than polyethylene.

It is evident that when the reflector reaches a certain thickness, graphite produces the maximum energy deposition. Therefore, graphite is selected as the reflector material for subsequent studies.

The effect of the reflector shape on the energy deposited by a single photon

Figure 6 (b) illustrates the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the high-carbon steel sample, with a 90 cm source-to-sample distance, using a group B irradiated sample. The radiation source is a 60Co source with a thickness of 1 cm, and the reflector is either a cubic shell or a cylindrical graphite shell. The results show that when the reflector takes a cylindrical shape, the energy deposited by a single photon in the irradiated sample’s bottom layer is higher than that of a cubic shell.

This phenomenon can be attributed to the geometric characteristics of the cylindrical shell-shaped reflector. First, photons that do not directly interact with the high-carbon steel sample have a shorter average path in the air due to the cylindrical shape, resulting in reduced energy loss. Additionally, the curvature of the cylindrical shell inherently focuses the reflected photons toward the center, increasing the number of photons that interact with the high-carbon steel sample through reflection. As a result, the photons reflected in the sample possess higher energy upon interaction, leading to greater energy deposition. On the other hand, since the cylindrical shell has a smaller volume than the cubic shell, it requires less graphite (approximately 4.5 tons). Therefore, depending on the graphite purity used, choosing the cylindrical shell reflector can save between $10,000 and $50,00036,37.

Therefore, from the standpoint of maximizing energy deposited in the underlying sample layer and optimizing material usage cost-effectively, the cylindrical shell-shaped reflector is the most advantageous option.

The effect of the distance from the radiation source to the high-carbon steel irradiated sample on energy deposited by a single photon

According to the optimization measures discussed above, the shape of the reflector is set as a cylindrical shell, the material is specified as graphite, and the radiation source is chosen as 60Co with a thickness of 1 cm. The source-to-sample distances vary between 30 cm, 50 cm, 70 cm, and 90 cm. As illustrated in Fig. 7(a), the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer of the sample decreases as the source-to-sample distance increases. This phenomenon can be attributed to two primary factors. First, the greater the source-to-sample distance, the longer the photon must travel through the air before interacting with the high-carbon steel sample, which reduces the photon’s energy. Second, most energy contribution comes from photons that reach the sample layer. As the source-to-sample distance increases, the solid angle between them decreases, allowing fewer photons to reach the sample directly, ultimately reducing the total energy deposited in the high-carbon steel sample.

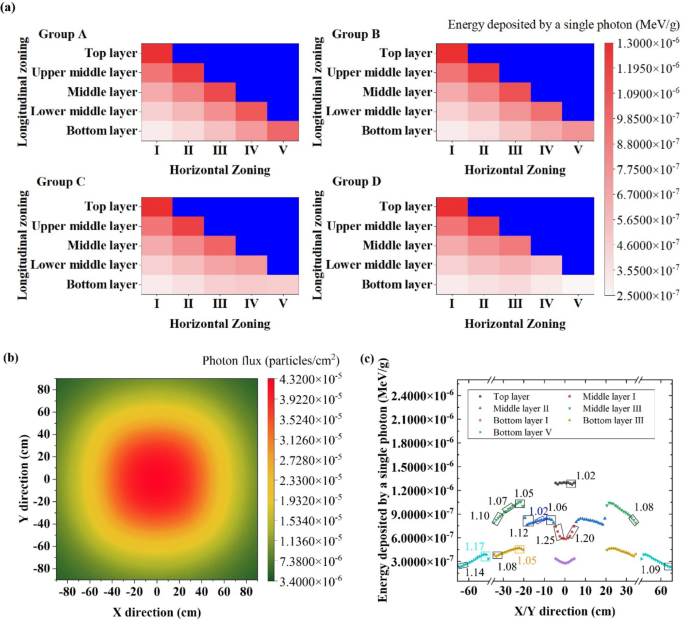

In practical irradiation sterilization, it is essential to consider the sterilization dose and the dose uniformity ratio (DUR), which is the ratio of the maximum to minimum absorbed dose within the irradiated product38. To investigate the effect of distance on the DUR, each layer of the high-carbon steel samples was divided into five zones along the horizontal direction. These zones, numbered I to V from the inner to the outer regions, are defined based on their dimensions as illustrated in the Fig. 7(b). The calculated energy deposited by a single photon within each zone of group A high-carbon steel samples at different source-to-sample distances is shown in the Fig. 7(c).

The results reveal that merely increasing the source-to-sample distance is insufficient to reduce the DUR to the commonly used value of 1.6 in irradiation practices39. In fact, prior studies have demonstrated that gamma irradiation up to 50 kGy does not compromise the integrity of surgical blades, where a DUR of 2 is acceptable. To address the high DUR from the surgical blades’ density, a secondary irradiation method can be used40. We set a DUR below the maximum allowable value, such as 1.6. The sterilization time for a single irradiation cycle is calculated based on the energy deposited by a single photon in the sample. After the first irradiation, surgical blades in the high-dose regions, which have reached the sterilization dose, are removed from the irradiation position. Meanwhile, blades in the low-dose regions, which have not yet reached the sterilization dose, either remain in place or are repositioned within the low-dose areas, depending on the relative dose levels. After placing unsterilized blades in the high-dose regions, they undergo the next round of irradiation.

Taking the A group source sample at a distance of 30 cm as an example, assuming a DUR setting of 1.6, the minimum energy deposition required from a single photon in high-carbon steel for the first irradiation round is 8.0725 × 10− 7 MeV/g. After one irradiation, the top layer, upper middle layer, middle layer II and III zones, lower middle layer III and IV zones, and bottom layer V zone can be removed from the irradiation device. However, the middle layer I zone, lower-middle layers I and II zones, and bottom layers I, II, III, and IV zones require a second irradiation. Since the energy deposited a single photon in the middle layer I and bottom layer I zones differs significantly, the surgical blades in these two zones can be swapped before the second irradiation. Similarly, the surgical blades in the bottom layer IV zone can be swapped with those in the bottom layers II and III zones, ensuring more uniform irradiation.

Thus, the method of zonal dual-round irradiation effectively mitigates the DUR constraints imposed by the source-to-sample distance. To maximize photon energy deposition in high-carbon steel samples, a source-to-sample distance of 30 cm was selected.

The effect of the high-carbon steel irradiated sample size on energy deposited by a single photon

When the reflector is configured as a cylindrical graphite shell, the radiation source is set as 60Co with a thickness of 1 cm, and the source-to-sample distance is fixed at 30 cm, the energy deposited by a single photon in different regions for four groups of samples (with dimensions listed in Table 2) is illustrated in Fig. 8(a). It can be observed that the energy deposited by a single photon in zone V of the bottom layer decreases significantly as the sample size increases.

This phenomenon is because as the size of the high-carbon steel sample increases, the photons interacting with the sample have more opportunities to interact with it, thus transferring more total energy to the sample. However, the simulation, which uses a volume source composed of multiple isotropic point sources, shows the photon flux 30 cm below the radiation source, as depicted in Fig. 8(b). As Fig. 8(b) demonstrates, the number of photons traveling in the horizontal direction decreases as the distance from the vertical axis within the irradiation device’s reflector increases. This observation is consistent with earlier findings by Diming Z32. Consequently, when the bottom sample layer becomes too large, although the number of photon interactions with the high-carbon steel sample increases, the peripheral regions of the sample interact less with the photons compared to areas near the vertical axis. As a result, the deposited energy in the peripheral regions is lower. When normalized, it shows that the energy deposited by a single photon decreases as the sample size increases beyond a certain point.

This highlights that simply increasing or reducing the size of the high-carbon steel sample is not a practical approach for optimizing irradiation. The characteristics of the radiation source must be considered to determine the appropriate sample size for effective irradiation. Since the energy deposited by a single photon in the bottom layer V of the group D high-carbon steel sample is too low, we chose the group C as the subject for further sterilization time calculations. This ensures effective sterilization and uniform irradiation while maximizing the processing capacity per cycle. A DUR of 1.6 was roughly set, with the single irradiation time determined by the energy deposited by a single photon in the middle layer II. To evaluate the uniformity of blades with different lengths after a single irradiation, 150 cubes with a side length of 1 cm were sampled diagonally across various regions, including 10 from the top layer, 70 from the middle layer, 10 from bottom layer I, and 30 each from bottom layers III and V. For surgical blades with dimensions of 3 cm and 4 cm, the DUR was calculated using continuous sets of 3 and 4 cubes, as shown in Fig. 8(c). The energy deposited by a single photon in each small cube within the same region varies. For instance, in the middle layer II region, starting from the cubes near layer I, the energy deposited by a single photon initially increases, then gradually decreases, but reaches its maximum in the cubes near layer III. This variation arises from the interplay between the photon flux distribution in the horizontal plane and the stacking effect of high-carbon steel layers. The 4 cm surgical blades exhibited greater dose non-uniformity than the 3 cm blades in certain regions, such as the outer edge of the bottom layer V, due to their larger spatial coverage. Within the evaluated regions, the DUR for the 4 cm blades peaked at 1.25 when placed at the edge of middle layer I, and reached its minimum of 1.02 when placed in middle layer II or the top layer. These results highlight the importance of selecting the placement area based on blade size. For secondary irradiations, in addition to repositioning the blades, horizontal rotation is recommended to improve dose uniformity.

In the group C, the minimum energy deposited by a photon in middle layer II was 7.6493 × 10− 7 MeV/g, while the maximum energy deposited in the top layer was 1.3030 × 10− 6 MeV/g, resulting in a DUR of 1.70, which is below the allowable maximum of 2. Accordingly, 7.6493 × 10− 7 MeV/g was used to calculate the single irradiation time.

Estimation of the shortest radiation sterilization time

Using the parameters from the optimized irradiation device model, with a 20 cm thick graphite cylindrical shell reflector and a source-to-sample distance of 30 cm, C group high-carbon steel samples were selected (with layer sizes of 10 × 10 cm2, 40 × 40 cm2, 70 × 70 cm2, 100 × 100 cm2, and 130 × 130 cm2). The minimum energy deposition of 7.6493 × 10⁻⁷ MeV/g in the middle layer II was used to calculate the irradiation time for a single exposure. At this point, the sample’s DUR is 1.7, which is below the maximum allowable value of 2.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)41 and the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (formerly the Ministry of Health)42 recommend a standard sterilization dose of 25 kGy to ensure a high level of sterility, especially in cases where the contamination level or the type of microorganisms present cannot be determined. Accordingly, 25 kGy is used as the lethal dose for microorganisms in this study to calculate the required sterilization time. The radiation sterilization dose is calculated as follows:

$${D_T}=\frac{{{H_T}}}{{{w_R}}}$$

(4)

In Eq. (4), DT is the radiation sterilization dose, HT is the standard sterilization dose of 25 kGy, and wR is the radiation weight factor of gamma rays, 120. Therefore, the radiation sterilization dose is 25 kGy. The sterilization time is:

$$t=\frac{{{D_T}(Gy)}}{{d(MeV/g) \times 1.6 \times 10{}^{{ – 19}} \times 10{}^{3} \times 10{}^{6} \times A(Bq) \times n \times 60}}(\hbox{min} )$$

(5)

In Eq. (5), d represents the energy deposited by a single photon, n represents the number of photons released per decay, and A represents the intensity of the photon. The 60Co source releases two gamma photons per decay. For a 60Co source used in medical sterilization devices, with an activity of 1.5 × 105 TBq43 and under the conditions specified (1 cm thick 60Co source, 20 cm thick cylindrical graphite reflector, 30 cm source-to-sample distance), the irradiation time for a single exposure of C group high-carbon steel samples (with layer sizes of 10 × 10 cm2, 40 × 40 cm2, 70 × 70 cm2, 100 × 100 cm2, and 130 × 130 cm2) was calculated to be 11.57 min. This means the total irradiation time of 23.14 min will be sufficient to achieve full sterilization of the surgical blades.

Moreover, suppose a more powerful 60Co source with an activity of 5.6 × 105 TBq, as permitted by the IAEA for medical sterilization devices43, is used. In that case, the sterilization time for medical surgical blades can be significantly reduced to 6.20 min. This reduction is due to the increased activity of the source, which releases more photons and, therefore, deposits more energy in a shorter time, achieving the required sterilization dose faster.