An overview of key results and corresponding methods are shown in Table 1.

Search and selection

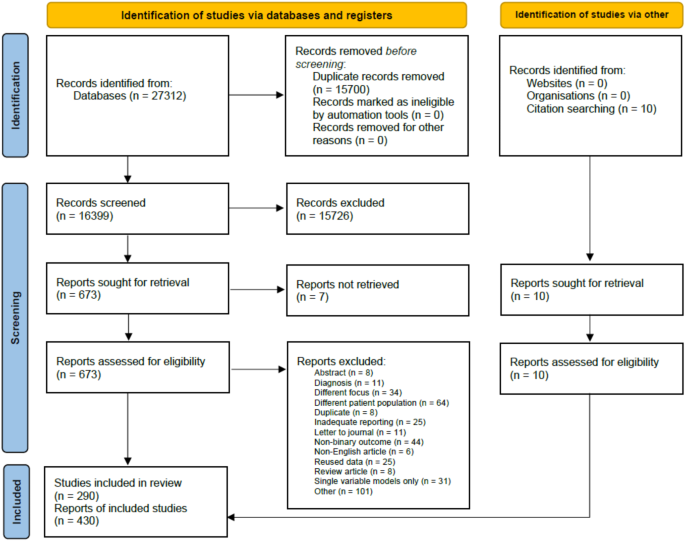

We identified 27,312 studies by systematically searching the five medical databases above (Medline: 13096, Embase: 5385, Cochrane and Cochrane Covid: 3411, Scopus: 5420). 16,399 records were screened, first based on the title and abstract, then on full texts. Ultimately, out of the 683 studies retrieved, 280 from database search and 10 from citations were eligible for data extraction. The selection process is summarised in Fig. 1. These 290 studies reported 430 independent evaluations of severity prediction tools.

Descriptive characteristics of included studies

The 430 prediction tool evaluations used data from a total of 2,817,359 patients, with a mean sample size of 6,552 and a median of 320. Summary statistics for the three main tool types are given in Table 2; individual study characteristics are detailed in Supplementary Data S1, and references are listed in Supplementary References S1.

Of the 430 studies, 221 (51.4%) use mortality—either after 30 days of hospital admission or the final data collection date—to define severe cases and survivors as non-severe cases of COVID-19. Most of the other 209 studies use one of the following definitions: (1) moved to ICU, (2) needed some type of mechanical ventilation, or (3) the composite definition of the National Health Commission of the Peoples’s Republic of China10: having respiratory distress, respiratory rate ≥ 30 times/min, oxygen saturation ≤ 93%, PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mm Hg. We grouped these non-mortality severe outcome definitions as none of the analyses showed substantial differences.

Performance of severity prediction tools

From the 290 studies that provided enough data to assess Area Under receiver operating characteristic Curve (AUC), 430 independent evaluations could be extracted as many studies used different patient groups to develop and validate tools. 61.2% of tools are either preexisting clinical severity scores used as is or modified for COVID-19 or based on the simple logistic regression. Thus, most tools are linear classifiers that are easy to use and interpret, achieving a pooled AUC of 0.855 (SE 0.009) based on a random-effect meta-analysis. Without neural networks, machine learning tools have a pooled AUC of 0.891 (SE 0.008), while for neural network-based tools, the pooled AUC is 0.900 (SE 0.015). Tools in the latter two groups significantly (p < 0.001) outperform linear methods on average. However, substantial residual heterogeneity (I2 = 95.59%, and R2 = 5.84%) shows that other important factors affect performance besides the mathematical structure of the tools. (See detailed regression output in Supplementary Table S1 and results in Supplementary Table S2.)

Identification of confounders of tool performance

In total, 24 potential variables were identified as possible confounders for measuring the effect of tool type on severity prediction performance. (The complete list of variables can be found in Supplementary Table S3.) Out of all candidates, 13 proved to have positive explained variance in out-of-bag samples in 99% of the 200 replications of the MetaForest model with 5000 trees: region of patient population, total number of patients included in the study, rate of severe patients, how severity was measured (as composite severity or as mortality) in the study, the time of the study, and the inclusion of age, C-reactive protein (CRP), respiratory rate, white blood count (WBC), measurement of blood gases, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and albumin as input variables of the prediction tool. Partial dependence plots suggested a quadratic relationship between AUC and the rate of severe patients in the study. (See replication importance values in Supplementary Fig. S1.)

Area under the curve for severity prediction

After the preselection of confounders by the MetaForest algorithm, we used a mixed-effects meta-regression to estimate effect sizes and select a more parsimonious model by the permutation of the preselected variables. We opted for a model with 3 variables that retain an R2 of 35.12% compared to the full model’s 38.31%. As Table 3 shows, the 3 variables that have a significant effect are the region of the patient population, the rate of severe patients (and its squared value because of the quadratic dependence), and the inclusion of C-reactive protein (CRP) as an input variable of the prediction tool. (The results of the univariate analyses for the three confounders of AUC can be found in Supplementary Table S4.)

As the reference setup, using a logistic regression prediction tool on European patients without CRP as input data and a 25% severity rate (the mean in collected data), the expected AUC is 0.857 (SE 0.010). A simple clinical score would have a significantly lower pooled AUC by 0.029 (SE 0.012), while neural network-based tools have a higher pooled AUC by 0.039 (SE 0.020). Thus, the difference in AUC between the best and worst tool types is 0.068 on average. For patients from China, prediction performance is better than that of Europeans by 0.069 (SE 0.009), and using CRP increases the expected pooled AUC by 0.022 (SE 0.007). To illustrate the magnitude of differences in performance, the expected AUC of a simple clinical score used in a European setting with 40% severity rate, not considering CRP, is 0.780 (SE 0.012), while a Neural Network in a Chinese setting with 5% severity rate and using CRP values is 0.998 (SE 0.020). The first tool is usually labelled fair, but the second is excellent11.

Sensitivity and specificity of severity prediction

Studies are heterogeneous in their method of choosing sensitivity and specificity, but this is independent of tool type; thus, a comparison is valid. Values in Table 4 are adjusted for the region of the patient population, the rate of severe patients, and the inclusion of CRP as an input for the prediction. Because of insufficient reporting by the original studies, only 124 could be included in this analysis.

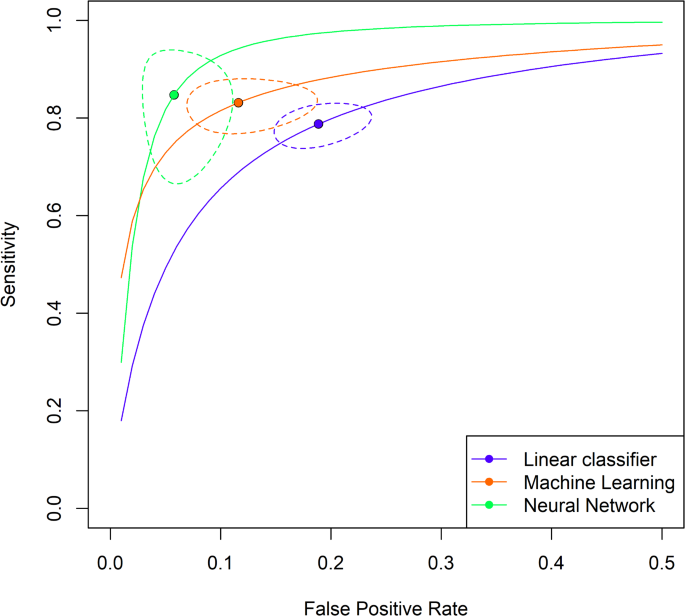

Supplementary Table S5 shows that the three tool types have significantly different mean sensitivity and specificity values. Linear classifiers are the least performant, with close to 72% sensitivity and 80% specificity. Meanwhile, neural network-based tools are the best, with a mean sensitivity and specificity of more than 75% and 91%, respectively. Study-level adjusted mean values are displayed in Fig. 2.

Study-level adjusted mean sensitivity and false positive rate. The figure shows the study-level adjusted mean sensitivity and false positive rate by tool type with 95% confidence interval for the mean and estimated hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic curves (HSROC). (Note that the false positive rate goes up only to 50% on the figure.)

The same ordering of tool types can be observed: linear tools are the worst, machine learning tools are better, and neural networks are the best. Table 5 shows a hypothetical patient population of 700 million with 10% severe cases. Linear classifier-based tools give a positive test result for 271 M patients and correctly identify 44 M, machine learning tools produce 227 M positives, out of which 49 M are true positives. In contrast, Neural networks give a positive result for 144 M out of which 47 M are true positive cases.

Comparative analysis for tool development

Input modalities

Investigating the different types of input data modalities, we found that the ratio of tools that rely on only tabular data is 78.4%. Basic demographic data and laboratory measurements are used in about two-thirds of cases for both data types, 74.6% and 74.0%, respectively. Imaging data is used in 21.6% of cases, and none of the predictive tools incorporated text data. Using the mixed-effects meta-regression separately for the three main tool types, Table 6 shows that for linear methods, the use of laboratory data and imaging data both increase AUC, but only when one of these is used and not both, as indicated by the significance and effect size of the interaction term for lab and imaging. For machine learning or neural network-based tools, adding imaging or laboratory data to demographic and other clinical input data does not change the estimated pooled AUC significantly, suggesting that machine learning and neural network-based tools gain their classification performance benefit more from the non-linear mathematical structure than specific input data.

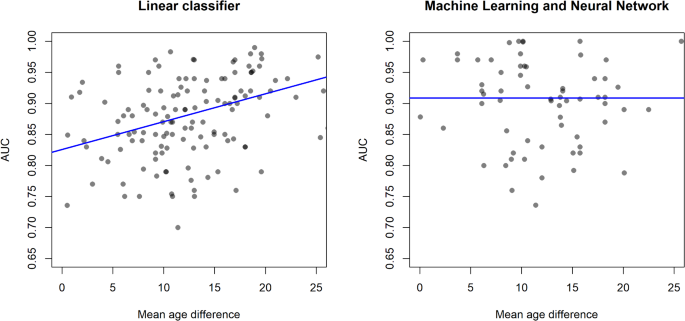

We analysed AUC as a function of the mean age difference between severe and non-severe patient groups, where the latter serves as a proxy for the classification problem difficulty, including the number of patients, region, and rate of severe patients in the model as well. As mean age difference is an aggregate value, ecological bias may be present, but our separate patient-level analysis suggested this is not an issue. If the mean age difference is large, the two patient groups are easily separated by demographics, making the mathematical structure of the prediction tool or other input data less important. In such a setting, simple linear methods are expected to work well. As age is highly correlated with both disease severity and many clinical and laboratory measurements12, if the mean age difference is small, the two patient groups are not expected to be easily separable. Figure 3 shows that for linear tools, AUC is expected to significantly increase with an increase in mean age difference (slope of 0.0045 AUC/year), while machine learning or neural network-based tools do not display such a relationship. The number of patients in the dataset has a small but significant negative association with AUC for linear methods, which means prediction tools from larger studies have a lower performance. The dependence of AUC on the number of patients is not significant for machine learning and neural network-based tools, confirming that the increase in performance comes from the mathematical structure and not additional data.

131 studies had data for linear classifiers and 67 for machine learning tools. The estimated regression coefficients are in Table 7.

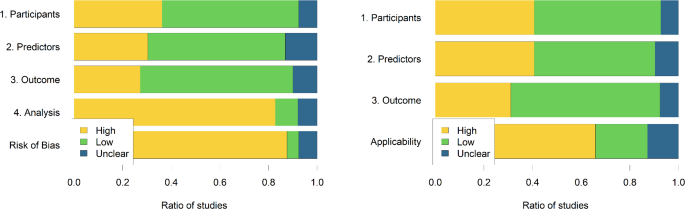

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias and applicability assessment is shown in Fig. 4, as proposed by Moons et al.13. There is a high risk of bias overall for close to 88% of studies, predominantly because of the high risk of bias in the analysis phase. The two most often encountered errors in the analysis were (a) using univariate association measures between potential explanatory factors and the severity outcome to select variables to be included in a multivariate prediction tool and (b) p-value-driven variable selection. Handling missing data is also an issue, as most studies opt to exclude patients who have “too many” missing values, and even if missing values are imputed, detailed statistics comparing original and imputed values are not provided. Overfitting is primarily avoided by separating training and validation sets of patients, but performance metrics are only reported on separate test sets if data is gathered from multiple sources.

Supplementary Fig. S2 shows funnel plots for subgroups by main tool types and geographic region of the patient population, and corresponding Egger’s test results can be found in Supplementary Table S6.