Synthesis and characterization of TiOx@C

First, Ti3C2 nanosheets were synthesized by a chemical exfoliation method according to the previous literature29. In general, Ti3C2 nanosheets are considered to be highly sensitive to strong oxidants due to their large specific surface area, making active Ti atoms easily to be oxidized to titanium oxide30. Here, we treated the Ti3C2 aqueous dispersion with H2O2 to obtain the oxidation product (Fig. 2a). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images show the microstructure transformation of Ti3C2 before and after H2O2 oxidation (Figs. S1, Supplementary information). The final product, referred to as TiOx@C, displayed a carbon layer with a silk-like structure in which TiOx dots of 2 to 5 nm were uniformly distributed, thus forming the TiOx@C nanocomposites (Fig. 2b). The stability of TiOx@C in aqueous solution was further investigated. Digital photographs, TEM images and UV-vis spectra results show that the morphology and composition of TiOx@C in water remained unchanged for up to 30 days (Figs. S2 and S3, Supplementary information). Furthermore, TiOx@C exhibits excellent dispersion in aqueous solution, saline, and LB Broth, thereby making it a promising nanomedicine for antimicrobial therapy (Figs. S4, Supplementary information).

a Schematics for the synthesis of TiOx@C nanocomposite. b TEM images of TiOx@C nanocomposites scale bar, 50 nm. c HRTEM image of TiOx@C, scale bar, 2 nm. The white arrows indicate the lattice distortion. n = 3 samples with similar results. XRD pattern (d) and Raman spectra (e) of Ti3C2 and TiOx@C. (f–i) EPR spectra (f) and Ti 2p (g), O1s (h), C 1s (i) XPS profiles of TiOx@C.

The corresponding lattice planes of TiOx quantum dots are observed by high-resolution TEM (HRTEM), indicating that the lattice distortion defects are conspicuous (Fig. 2c). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mappings by TEM and SEM demonstrate that the Ti, O, and C elements are uniformly distributed throughout the nanohybrids, revealing that the TiOx are evenly decorated on the carbon layer without significant aggregation (Figs. S5–6, Supplementary information). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the precursor Ti3C2 and TiOx@C show that the disappearance of 2θ peak at 9.5° after the formation of TiOx@C, indicating that the layered structure no longer existed (Fig. 2d)29. While TiOx@C shows no obvious indication of crystallinity, due to the amorphous structure of carbon layer. Raman results reveal that the characteristic peaks of Ti3C2 completely disappeared in the Raman spectra of TiOx@C, while the different peaks at 153.9 and 623.5 cm−1 can be observed, which correspond to the symmetric stretching and bending vibration of O-Ti-O in Ti3O5 respectively (Fig. 2e)31. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) was used to confirm the presence of oxygen vacancies (OVs). The EPR spectrum of TiOx@C displays a g value of about 2.004, confirming the presence of OVs in TiOx (Fig. 2f)32. As evidence for the presence of multivalent titanium grew, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was used to verify the chemical state of TiOx@C. In the Ti 2p spectrum (Fig. 2g), the characteristic peaks of Ti 2p1/2 at 463.8 eV and Ti 2p3/2 at 458.2 eV indicate the Ti3+ in TiOx, and the characteristic peaks of Ti 2p1/2 at 464.8 eV and Ti 2p3/2 at 458.8 eV correspond to Ti4+, confirming the multivalent state of Ti in TiOx. The O1s spectrum shows four characteristic peaks centered at 530.0, 530.7, 531.7 and 532.6 eV, corresponding to the Ti-O bonds, hydroxylated surface, the presence of OVs and adsorbed moisture respectively, which is consistent with the EPR results (Fig. 2h). The C 1 s spectrum exhibits two peaks at 284.8 and 287.5 eV, corresponding to the C-C and C-O bonds in the carbon layer, respectively (Fig. 2i)33. The high intensity of the C-C peak indicates the enhanced electrical conductivity of TiOx@C.

To gain deeper insight into the effect of structural evolution on the performance of Ti3C2, first-principles DFT calculations were performed, and the optimized models were provided (Figs. S7, Supplementary information). According to the partial density of states (PDOS) calculation results, the pristine oxygen-capped Ti3C2 shows metalloid properties; above the Fermi level (Ef), the dominant contribution to the DOS comes from the d orbitals of Ti atoms, while below the Fermi level, the prevailing contribution to the DOS comes from the p orbitals of the O atom orbitals. Besides, the PDOS of Ti 3 d of TiOx exhibits a stronger intensity around the Fermi level, thus improving conductivity and promoting the electron transfer of TiOx (Figs. S8, Supplementary information). It is typically believed that the arc radius in electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) is proportional to the resistance of the material; a smaller arc radius indicates a lower electron transport resistance in the material34. As shown in Figure S9, the lower electrochemical impedance of TiOx@C indicates a stronger electron transport capability than Ti3C2.

Antibacterial performance of TiOx@C

Inspired by the unique structure and improved electron-donating ability of TiOx@C, the potential of TiOx@C as a bactericidal agent was further investigated. Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), which is a major bacterial human pathogen representative of gram-positive bacteria (G + )35, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) that is one of the top-listed pathogens causing hospital-acquired infections36, representing for gram-negative bacteria (G−), were used as model bacteria. As shown in Fig. 3a–c, TiOx@C exhibited broad-spectrum and concentration-dependent antibacterial activity, while the titanium-based nano-antibacterial agent Ti3C2 nanosheets and TiO2 nanoparticles showed negligible intrinsic antibacterial performance, which depend on additional external light irradiation to generate photothermal/photodynamic therapy as previously reported37,38. The results suggest that the specific electronical property of TiOx@C with abundant oxygen vacancies and multivalent states contributes to its antimicrobial activity. Notably, P. aeruginosa was more easily eradicated than S. aureus when the concentration of TiOx@C was increased to 30 μg mL−1, which highlights the potential strain-specific bactericidal mechanism of TiOx@C. Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) was used to observe the viability and cytotoxicity of bacteria stained by NucGreen and EthD-III. EthD-III is a cell membrane-impermeable nucleic acid dye that can determine bacteria with membrane damage. The CLSM images demonstrated the concentration-dependent antibacterial performance of TiOx@C (Fig. 3d). Then, the bacterial growth inhibition effect of TiOx@C was determined. The results demonstrate that TiOx@C inhibited the growth of S. aureus by 57.3% and P. aeruginosa by 64.9% at a concentration of 100 μg/mL for 24 h. Therefore, the minimum inhibitory concentration that inhibits 50% of the bacteria (MIC50) of TiOx@C for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa is 100 μg/mL (Figs. S10, Supplementary information). It can be found that TiOx@C inhibited the growth of S. aureus by 94.2% and P. aeruginosa by 91.6% at a concentration of 200 μg/mL for 24 h. Therefore, the minimum inhibitory concentration that inhibits 90% of the bacteria (MIC90) of TiOx@C for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa was 200 μg/mL.

a Representative optical images of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa colonies formed on LB agar plates after various treatments and (b, c) the corresponding colony counting results. n = 3, biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test was used to analyze multiple groups. NS, not significant. d CLSM images of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa stained with NucGreen (EX488) and EthD-III /PI (EX532) after different treatments, scale bar, 40 μm. Green color indicates live bacteria, and red color indicates membrane-damaged bacteria. n = 3, biological replicates with similar results. e Representative optical images of biofilms stained by crystal violet after the treatment by TiOx@C at varied concentrations. (f, g) The corresponding quantitative results of S. aureus biofilm (f) and P. aeruginosa (g) biofilm. n = 4, biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Considering the accelerated evolution of bacterial AMR against antibiotics, we further evaluated whether prolonged exposure to TiOx@C nanocomposites would similarly lead to the acquisition of bacterial resistance. The antibacterial efficacy of TiOx@C was evaluated by screening S. aureus and P. aeruginosa strains for a period of 21 days at sub-MIC90 values39. The results demonstrate that TiOx@C exhibited a prolonged antibacterial effect without the induction of resistance (Figs. S11 and S12, Supplementary information). A growing number of studies have revealed that nanomaterials can induce bacterial resistance through a range of mechanisms, such as Ag NPs40, TiO2 NPs41, and CNTs42. It is notable that TiOx@C has two components which have parallel correspondences to independent bacterial targets i.e., the bacterial cell wall, the electron transport system and redox homeostasis, which can achieve the synergy of the multiple independent bactericidal mechanisms in circumventing bacterial drug resistance8.

Biofilms exhibit a higher prevalence of multidrug resistance to most clinically available drugs, which is a crucial issue needing to be tackled43. Unfortunately, extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) bound to the cell surfaces of the biofilm can hinder the interaction of nanomaterials or drugs with the biofilm, thus reducing their germicidal efficacy44. Excitedly, it has been reported that boosted electron transfer between nanomaterials and bacteria can destroy the EPSs and eliminate biofilms without developing drug resistance45. The crystal violet method was performed to qualitatively and quantitatively evaluate the ability of TiOx@C to eliminate biofilms. The results indicate that the amount of crystal violet adhered to the biofilm treated by TiOx@C was significantly reduced, confirming that such material could effectively eliminate both S. aureus and P. aeruginosa biofilms (Fig. 3e). As shown in Fig. 3f, g, the quantitative results demonstrate that the anti-biofilm activity of TiOx@C exhibits a concentration-dependent manner, and the elimination rate of P. aeruginosa biofilm could reach up to 92% at a concentration of 400 μg mL−1.

Bacterial cell wall-specific performance of TiOx@C

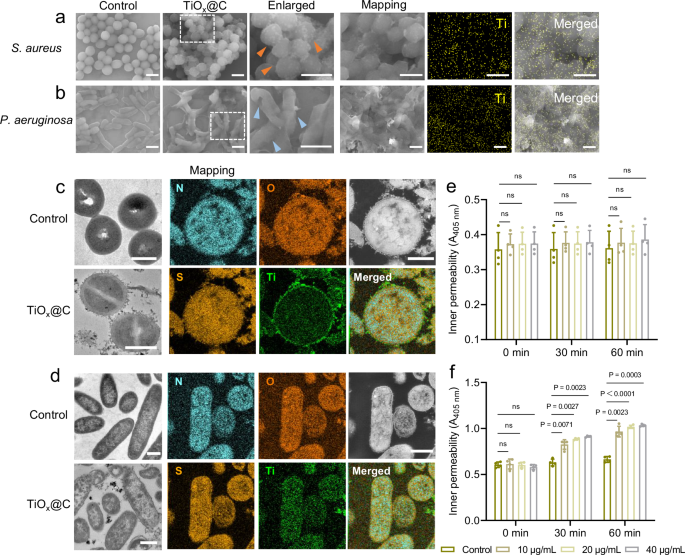

The morphological changes of the bacteria before and after co-incubation with TiOx@C were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The SEM images exhibit that the initial cell walls of S. aureus are roughened after TiOx@C treatment, indicating that S. aureus were wrapped on the surface by the fibrous carbon layers (marked by orange labels) (Fig. 4a). As shown in the SEM images of P. aeruginosa, the original smooth cell walls become shrunk and the morphology exhibit shriveled after co-incubation with TiOx@C, indicating that TiOx@C has led to the loss of bacterial cytoplasm, shrinkage and/or deformation of bacterial membranes of P. aeruginosa. The corresponding elemental mapping demonstrates that the TiOx quantum dots were distributed uniformly on the bacterial surfaces to trap and disarm bacteria (Fig. 4b). The differences between the cell wall of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa after TiOx@C treatment inspire us to investigate its potential bacterial cell wall -specific antibacterial mechanism.

a, b SEM images and elemental mapping of S. aureus (a) and P. aeruginosa (b) after various treatments, scale bar, 1 μm. n = 3, biological replicates with similar results. c, d Bio-TEM images and elemental mapping of S. aureus (c) and P. aeruginosa (d) before and after TiOx@C treatment, scale bar, 500 nm. n = 3, biological replicates with similar results. e, f Permeability of bacterial membrane determined by ONPG assay and protein leakage analysis of S. aureus (e) and P. aeruginosa (f) after various treatments. n = 4, biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test was used to analyze multiple groups. NS, not significant.

Given the above hypotheses of the potential bacterial cell wall-specific antibacterial activity of TiOx@C, the intrinsic antibacterial mechanisms were further investigated. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) is a powerful tool for obtaining in-depth understanding of microbial morphology and structural details46. The AFM results show that the smooth surface of S. aureus became rough after TiOx@C treatment, and the corresponding root mean square roughness (Rq) increased significantly, which was consistent with the SEM results, implying that TiOx@C nanomaterials were extensively attached to the surface of the S. aureus bacterium (Figs. S13a, Supplementary information). In contrast, the surface roughness of P. aeruginosa did not change significantly, instead, the thickness of the bacterium is markedly reduced (Figure S13b, Supplementary information). The three-dimensional morphology-reconstructed images intuitively reflect the deflation and indentation of the bacteria after TiOx@C treatment, due to the leakage of bacterial contents (Figs. S14, Supplementary information). Bio-TEM observation was performed to further visualize the details of the internal structure of microbial cells after exposure to TiOx@C, and localize the position of TiOx@C within different bacteria. It can be observed that the TiOx@C adhere uniformly and tightly attached to the surface of individual S. aureus bacteria, showing minimal ultrastructural and morphological changes. The elemental mapping images more intuitively exhibit that the carbon networks of TiOx@C were entangled with the peptidoglycan (the major component of G+ cell wall) and close to the surface of the S. aureus inner membrane due to the outer thick peptidoglycan layer of G+ bacterium (approximately 20 ~ 40 nm), thus the carbon networks were blocked to get into the phospholipid bilayer of the bacterial inner membrane due to the size effect (Fig. 4c)47,48.

In contrast, P. aeruginosa with a much thinner peptidoglycan layer (~3 nm) treated with TiOx@C displayed significant morphological changes, including disruption of the cell wall, areas of clear cytoplasm, leakage of cytoplasm, and plasmolysis. In P. aeruginosa, the hydrophobicity and polarity of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) of its cell envelope drastically reduce the membrane permeability49. It has been widely reported that nanomaterials with unique morphology such as nanowire or nanorods can cause mechanical damage by disrupting the bacterial cell membrane or cell wall, which in turn kills the bacteria50,51,52. However, such mechanical damage largely depends on the angle of interaction of material with bacteria, which greatly limits in vivo applications. In our work, The elemental mapping results show a uniform distribution of Ti element on the bacteria, suggesting the carbon network of TiOx@C enables to penetrate the bacterial envelope and further enter the bacterium due to the strong hydrophobic interactions between the large number of C-C bonds, finally disrupting the bacterial membrane significantly (Fig. 4d)53. The interaction between TiOx@C and bacterial membrane can be further confirmed by detecting the permeability of the bacterial membrane using o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG). As a result, the permeability of the bacterial membrane of P. aeruginosa elevated significantly with increasing concentration and prolonging incubation time after exposure to TiOx@C (Fig. 4f), while those of S. aureus showed negligible change (Fig. 4e).

Next, the detailed changes after TiOx@C treatment of the cell envelope were further elucidated at the micro/nanoscale by small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). The exhibited SAXS profile can be divided into three regions: Region I represents the overall size of the bacterial cell in the system, including the core-shell structure. Region II contains information about the cell wall and its thickness, while region III reveals the structural arrangement of groups of objects (e.g., DNA, ribosomes, and proteins) in the cytoplasm54. As a result, the scattering curves of TiOx@C-treated S. aureus shifted to higher q values in region I and to lower values in region II and III, suggesting that the overall structure of the bacteria has become larger and looser, while the thinning of the bacterial wall may be accompanied by denaturation and loss of contents of the bacterial cytoplasm (Fig. 5a). On the contrary, the scattering curves of treated P. aeruginosa shifted toward lower q values in regions II and III, which implies that the membrane structure and cytoplasmic contents of the bacteria were significantly disrupted (Fig. 5b). Meanwhile, the protein leakage of bacteria was determined by BCA Protein Assay Kit. It could be found that the P. aeruginosa individuals suffered membrane damage with a decrease in total protein amount, which indicates the significant protein degradation (Fig. 5c, d).

a, b SAXS scattering profile for the dispersions of S. aureus (a) and P. aeruginosa (b) before and after TiOx@C treatment. c, d Protein leakage analysis of S. aureus (c) and P. aeruginosa (d) after various treatments. e The corresponding schematic illustrations of interactions of TiOx@C with Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacterial membrane. n = 4, biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test was used to analyze multiple groups. NS not significant.

In summary, the same antimicrobial agent would have varied binding interactions with different bacterial cell wall due to the size effect, which may lead to various antibacterial mechanisms against different bacteria. In the case of S. aureus, TiOx@C can merely be enriched in its much thicker peptidoglycan layer owing to the large sizes of carbon substrate. Thus, few of them could disrupt the inner membrane. For P. aeruginosa, TiOx@C is able to penetrate its lipopolysaccharide layer and the outer membrane due to hydrophobic interaction and further disrupts the thinner peptidoglycan layer to enter the bacteria, which is directly and strongly toxic to the bacteria (Fig. 5e).

Self-driven electron transfer in bacteria-TiOx@C interface

Compared to previous bacterial wall-specific antimicrobials15,16,17, TiOx@C was unable to enter S. aureus but still showed great bactericidal activity. As is known in literature, the electron transport chain (ETC) on the bacterial inner membrane plays a key role in physiological processes of bacteria such as metabolism and energy supply55. In recent years, interference/disruption of the bacterial electron transport chain has been applied as an emerging antibacterial strategy in a number of studies6,8. However, most of these are based on piezoelectric materials to achieve electron transport which require additional ultrasonic stimulation. Considering the unique electronic structure of TiOx, we further explored the potential self-driven electron transport in bacteria-TiOx interface. To investigate the electrochemical activity of the TiOx@C-bacteria systems, the cyclic voltammetry (CV) experiment was performed. As a result, the CV curves of S. aureus– TiOx@C exhibit a greatly increased current signal compared to untreated bacteria, while the CV curves of P. aeruginosa show negligible change before and after TiOx@C treatment (Fig. 6a). Subsequently, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was used to evaluate the ability of TiOx@C to boost electron transport capacity. As shown in Fig. 6b, the semicircle diameter (Rct) of the S. aureus– TiOx@C was significantly smaller than that of untreated S. aureus, indicating that the TiOx@C facilitates electron transfer, thus increasing the electrical conductivity of the S. aureus-TiOx@C systems. Similarly, no significant difference was found in the EIS profiles of P. aeruginosa before and after TiOx@C treatment.

a Cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of suspended S. aureus and P. aeruginosa after various treatments. b EIS spectrum of suspended S. aureus and P. aeruginosa after various treatments. c, d The corresponding INT-ETS assay outcomes containing UV-vis spectrum and quantitative ETS results of S. aureus (c) and P. aeruginosa (d) after various treatments. n = 3, biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test was used to analyze multiple groups. (e, f) The ATPase concentration of S. aureus (e) and P. aeruginosa (f) treated with TiOx@C. n = 3, biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test was used to analyze multiple groups. NS, not significant. (g, h) The ATP level of S. aureus (g) and P. aeruginosa (h) treated with TiOx@C. n = 3, biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test was used to analyze multiple groups. NS, not significant. (i) Structural optimization of heme c adsorption on TiOx@C and electron density difference plots at the heme c and TiOx@C interface from top view and side view.

It has been reported that nanocatalysts with similar TiOx structure exhibited efficient Fenton-like catalytic performance attributed to the abundance of surface defects and the presence of multivalent titanium56. The TiOx@C-mediated Fenton-like reaction was evaluated using a colorimetric method based on the degradation of methylene blue (MB) after selective ·OH trapping. It can be found that the MB absorption showed a significant decay after TiOx@C + H2O2 treatment, suggesting the production of ·OH radicals (Figs. S15, Supplementary information). Thus, we further measured the ROS levels of bacteria after TiOx@C treatment. The results indicate that the bacteria in the control group emitted negligible green fluorescence, while a concentration-dependent enhancement of fluorescence emission was observed in the TiOx@C-treated bacteria, possibly due to the excess ROS attack via a Fenton-like catalytic reaction57. (Figs. S16, Supplementary information).

Next, 2-para-(iodophenyl)-3(nitrophenyl)-5(phenyl)tetrazolium chloride (INT) was applied to detect the activity of the electron transport system (ETS). INT is a readily reducible reagent with its yellow color, which can accept hydrogen and electrons and be reduced to iodonitrotetrazolium formazan (INTF) turning purple; the rate of H+/e− transfer in the ETS can be quantified by the change in absorbance. The corresponding results demonstrate an increase of absorbance at 485 nm of S. aureus-TiOx@C system after addition of the INT detector. However, after prolonged co-incubation with TiOx@C, the absorbance decreased significantly. It can be found that TiOx@C is able to temporarily enhance the electron transport activity of S. aureus, which is attributed to the electronic property of TiOx and the superior electrical conductivity of carbon substrate to boost electron transport capacity in a short period of time, while the electronic activity was strongly inhibited upon prolonged incubation due to abnormal electron stacking (Fig. 6c). As to P. aeruginosa, a marked enhancement of ETS activity was observed over a short period, which could be attributed to two aspects. On the one hand, the ETS activity was improved by TiOx@C via boosted electron transport performance, and on the other hand, it may be related to the cell membrane disruption of P. aeruginosa, allowing more reductase enzymes in the bacterium to reduce INT. Notably, the decrease of U-values within 20 min of P. aeruginosa was greater than that of S. aureus, which indicates that P. aeruginosa suffers a mass death more quickly, corresponding to the results of the above experiments (Fig. 6d).

We then determined the stability of TiOx@C before and after exerting antimicrobial effects using XPS and MB degradation tests. The results show that the valence states of Ti in TiOx@C before and after co-incubation with S. aureus and P. aeruginosa has no significant changes, as the presence of carbon substrate is of great importance for maintaining the titanium in a relatively stable valence state or metastable state (Fig. S17, Supplementary information). And TiOx@C still exhibited significant Fenton-like activity after co-incubation with bacteria (Fig. S18, Supplementary information), suggesting that TiOx@C is able to inhibit bacterial growth efficiently over a long period of time. Moreover, the microbial ATP synthase concentration of the bacteria after various treatments was determined by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The results indicate that the ATPase level of both S. aureus and P. aeruginosa decreased significantly after co-incubation with TiOx@C (Fig. 6e, f). The ATPase activity of S. aureus decreased more rapidly in a short period of time due to the direct damage to the ATPase by the TiOx@C anchored on the bacterial membrane. Simultaneously, the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels of bacteria show the same trend as the decreased ATP synthase activity, indicating that the inhibition of the bacterial electron transport chain leads to insufficient motive force of the proton pump to enable ATP synthesis, resulting in a decrease in ATP levels (Fig. 6g, h).

Cytochrome c (cyt c) consisting of numerous heme c groups, an iron-containing biomolecule, plays a crucial role in the electron transport chain of bacteria, which facilitates the ordered transfer of electrons within the cell through its structural domains with iron-copper centers58. Therefore, we simulated the electron flow between heme c and TiOx@C. The electron accumulation and depletion regions are presented as yellow and blue areas respectively. Notably, the redistribution of electrons occurs at the interface between heme c and TiOx@C. The electron flow (e−) values of TiOx@C to heme c were further elucidated by Bader charge analysis (Fig. S19, Supplementary information). Consequently, a large accumulation of electrons occurred in the heme (iron center) structural domain, which is critical for heme c (Fig. 6i). The results demonstrate that TiOx@C is capable of overloading heme c with electrons and further inactivating cyt c activity, disrupting the bacterial electron transport chain and inducing bacterial death.

In summary, TiOx@C exhibits a synergistic electronic-mechanical bactericidal effect. For P. aeruginosa, TiOx@C can directly penetrate the bacterial membrane and cause severe mechanical damage. For S. aureus, TiOx@C is unable to directly damage the bacterial membrane, but can adhere to the bacterial membrane and disrupt the bacterial electron transport chain.

Specialized antibacterial mechanisms of TiOx@C against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa

Further, we performed a transcriptomic analysis on S. aureus and P. aeruginosa samples to investigate the effects of the membrane interaction-guided electron-mechanical intervention of TiOx@C against bacteria on gene expression and regulation. Preliminary identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the normal bacteria group and the TiOx@C-treated group was performed. The volcano plot shows that the TiOx@C-treated group had 968 DEGs compared to the untreated normal S. aureus (Fig. 7a).

a, f Volcano plots depicting fold changes and p-value per gene of S. aureus (a) and P. aeruginosa (f) comparing after TiOx@C treatment. b, g Differential gene GO enrichment column diagrams of enriched pathways of S. aureus (b) and P. aeruginosa (g). BP indicates biological process; CC indicates cellular component and MF indicates molecular function. c, h Heatmap depicting representative DEGs of different comparison groups of S. aureus (c) and P. aeruginosa (h); orange, upregulation; blue, downregulation; log2 fold change ≥ 1, Q values < 0.05. Key DEGs are marked on the right, n = 3, biological replicates. d, i Chordal graph presenting enriched GO pathway of the differentially represented genes in S. aureus (d) and P. aeruginosa (i) comparing after TiOx@C treatment. e, j Schematic mechanism of strain-specific antibacterial activity of TiOx@C against S. aureus (e) and P. aeruginosa (j).

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis reveals that DEGs in the S. aureus groups were involved in biological processes, cellular components and molecular functions especially in structural constitution of ribosome, extracellular region and translation, indicating that TiOx@C induced a stress response (Fig. 7b). It is noted that DEGs involved in electron carrier activity and ATP synthase activity were significantly down-regulated in S. aureus after TiOx@C treatment, which is consistent with the experimental results. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis shows that photosynthesis pathway involving proton motive and reducing forces and ATP synthase, was the most differentially expressed in S. aureus treated with TiOx@C (Figs. S20a, Supplementary information). And the corresponding eight genes involved in this pathway which are genetically associated with the composition and activity of the FoF1-ATPase were significantly down-regulated (Fig. S21, Supplementary information), demonstrating that the antibacterial mechanism of TiOx@C against S. aureus is to disrupt ATP synthase activity and interfere with the energy metabolism of the bacteria. Expression heat maps disclose that the expression of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)-related genes such as sdhA (representing flavoprotein subunit) and sdhB (representing iron-sulfur protein subunit) was downregulated, demonstrating the efficacy of TiOx@C in disrupting the electron transport chain of S. aureus, thus suppressing its respiratory chain (Fig. 7c)59. Moreover, the expression of the atpC gene, which encodes the γ subunit of the ATP synthase F1 complex that plays a pivotal role in cellular respiration in bacteria and energy supply system was significantly downregulated in the TiOx@C-treated group60. The chordal diagram depicting the enriched GO pathways of the DEGs exhibits that downregulation of key genes implies the disruption of bacterial ETCs due to blocked ATP synthesis and energy depletion. leading to S. aureus death (Fig. 7d). Cluster of homologous genes (COG) analysis is a common technique for microbial genome annotation and comparative genomics. The COG results indicated that genes related to translation, ribosomal structure and cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis were significantly downregulated, reflecting those physiological metabolic processes, such as cell wall structure, RNA transcription and protein synthesis were significantly suppressed in the bacteria after TiOx@C treatment (Figure S22a, Supplementary information).

Taken together, the antibacterial mechanisms of TiOx@C against gram-positive bacteria could be summarized as follows: Owing to the size effect, the fiber-like carbon substrate of TiOx@C entangles with peptidoglycan layer of S. aureus, which allows direct interface with the electron transport chain complexes on the cell membrane. Then, TiOx quantum dots with enhanced electron-donating ability exert electron flow into crucial enzymes of the ETC leading to electron stacking which disrupts the bacterial electron homeostasis. As a result, the damaged electron transport chain is unable to form the proton gradient for ATP synthesis. This disrupts bacterial metabolism and ultimately induces bacterial death (Fig. 7e).

The DEGs of P. aeruginosa differed significantly from those of S. aureus. In terms of P. aeruginosa, the treated group showed only 89 DEGs compared to the normal group (Fig. 7f). Specifically, GO enrichment analysis demonstrates that the oxidative stress response is of most differential expression in TiOx@C-treated bacteria, suggesting that TiOx@C induces oxidative stress in P. aeruginosa, which is consistent with the flow cytometry results (Fig. 7g). KEGG analysis results show that important pathways such as glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism output and lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis were enriched in TiOx@C-treated P. aeruginosa, revealing that TiOx@C induces a stress response in bacteria to generate adaptation to environmental changes (Figs. S20b, Supplementary information). Moreover, several genes related to oxidative stress and bacterial redox homeostasis were significantly upregulated (Fig. 7h). The chordal diagram depicting enriched GO pathways of the 6 representative DEGs exhibits that the upregulation of ahpC (known as alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C), ahpF (known as alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit F), katA and katB (encode for the enzyme catalase). In detail, the katB indicates that the bacteria have been damaged by oxidative stress, resulting in the upregulation of important enzymes involved in the detoxification of reactive oxygen species (Fig. 7i). The COG results indicated that genes related to the inorganic ion transport and metabolism which is largely related to the synthesis of oxidative stress-related enzyme were upregulated, verifying that P. aeruginosa suffered from oxidative stress after treatment with TiOx@C (Figure S22b, Supplementary information).

To sum up, the antibacterial mechanism of TiOx@C against Gram-negative bacteria can be summarized as follows: Due to the hydrophobic effect, the fibrous carbon substrate of TiOx@C can penetrate the outer and inner phospholipid bilayers of Gram-negative bacteria, further disrupting the bacterial membrane structure and altering membrane permeability. Then, TiOx quantum dots with unique electronic property introduce electron flow to macromolecules, proteins, metabolic enzymes in the bacterial cytoplasm to disrupt redox homeostasis, inducing bacterial oxidative stress. Finally, the membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is destroyed, resulting in severe oxidative stress damage and significant protein degradation and loss, which ends up in bacterial death (Fig. 7j).

Treatment of wound infection in vivo. Biocompatibility is of great significance for the development and application of biomedical nanomaterials. Thus, we investigated the cytotoxicity of TiOx@C using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. The results demonstrate that TiOx@C shows negligible cytotoxicity to PC12 and L929 cells even when the concentration was up to 300 μg mL−1 (Figs. S23, Supplementary information). In addition, for further biological applications, we verified the biosafety of TiOx@C to human cells. CCK-8 assay demonstrate the biocompatibility of TiOx@C to HacaT cells (Human Keratinocytes cells) (Figs. S24, Supplementary information). Considering the ability of TiOx@C to disrupt bacterial membranes, we further investigated the membrane integrity of the cells after co-incubation with the material. By staining the cells with PI dye, which is able to penetrate damaged cell membranes, it can be found that the cell membrane of HacaT cells incubated with TiOx@C was not disrupted (Figure S25, Supplementary information). The results suggest that TiOx@C is unable to penetrate the cell membrane of eukaryotic cells, due to differences in the composition of bacterial and eukaryotic cell membranes. It is well known that cholesterol (Chol), which regulates the bending rigidity of cell membranes is uniquely linked to cell evolution—it is universally absent in prokaryotic membranes and is present in differing amounts in eukaryotic membranes. The differential nature of the cell membrane serves as a barrier to prevent the carbon substrate from disrupting the integrity of the mammalian cell membrane, thus enabling microbial selectivity.

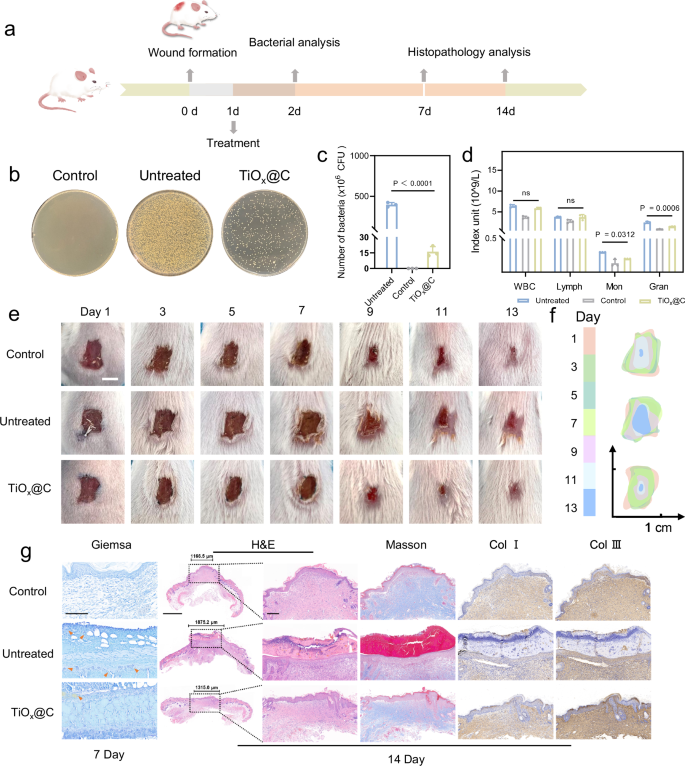

Inspired by the effective, multi-target antibacterial mechanism of TiOx@C, we constructed a S. aureus-infected wound infection model to assess the in vivo therapeutic efficacy. The in vivo experimental protocol is shown in Fig. 8a. As shown in Fig. 8b, c, the number of bacteria remaining in the infected lesions decreased significantly after treatments with TiOx@C. The quantitative results of plate counting demonstrated that the TiOx@C nanocomposites effectively eliminated 97% of the bacteria in the wounds, indicating that TiOx@C is promising as a potent antimicrobial agent for the treatment of wound infections. Also, the amounts of inflammatory cells in the peripheral blood of treated mice in response to infection were mostly close to normal levels, which demonstrates that TiOx@C can effectively alleviate infection-induced inflammation in vivo (Fig. 8d). Furthermore, no significant suppuration, edema and lesion expansion could be observed in TiOx@C-treated group, and the wounds were able to form scabs and heal faster within two weeks in comparison to the infected (untreated) group (Fig. 8e). The schematic morphological changes of the wounds in different groups over the 14-day course display the rapid wound healing in the TiOx@C -treated group, and such a rate of healing was comparable to that of the uninfected (Control) group (Fig. 8f), as evidenced by the time-dependent curves of wound areas (Figure S26a, Supplementary information). After wound modeling, all groups of mice exhibited a transient weight loss followed by an increase in body weight during the 14-day recovery monitoring period, during which the TiOx@C-treated and control groups showed a comparable weight gaining rate and the infected group grew at the slowest rate (Figs. S26b, Supplementary information).

(a) Scheme of the wound infection treatments. (b) Photographs of S. aureus colonies from infected tissues in 1 day post treatment. (c) Bacterial counting results corresponding to (b). n = 3, biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze multiple groups. (d) Inflammatory cell numbers in the blood of mice in different groups. n = 3, biological replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test was used to analyze multiple groups. NS, not significant. e Representative images of S. aureus-infected skin wound of mice after treatments for different days. Scale bar, 5 mm. n = 3, biological replicates with similar results. f Schematic diagrams of the wound size changes corresponding to (e). g Giemsa staining images on day 7, scale bar, 100 μm. Orange arrows indicate the S. aureus-infected area. H&E, Masson and IHC, Collagen I and III (Col I and Col III) staining images of wound tissues after various treatments on day 14, scale bar, 200 μm. Scale bar for smaller magnifications of H&E images is 1 mm. n = 3, biological replicates with similar results. The muscle fibers are presented as red, and the collagen fibers are presented as blue in Masson staining images. Brown color indicates the Col I and III-positive.

Accordingly, the remaining bacteria in the infected wound tissue could be further observed by Giemsa staining, which are negligible in the tissues on day 7 after TiOx@C treatment. Pathomorphological analysis of the wound tissues on day 14 was conducted (Fig. 8g). The hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining results indicate that the healing wound skin tissue in the TiOx@C-treated group had an intact tissue composition and follicle regeneration, with a distinct stratum corneum on the surface. However, in the untreated group, the incomplete skin structure could be observed accompanied by a noticeable scab attached to the surface of the wound. The Masson’s trichrome staining images suggest that more complete wound epithelium and the deposition of regenerated collagen fiber (stained blue) were observed in the infected wound tissue treated by TiOx@C. Additionally, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining outcome shows markedly large Collagen type I and type III (Col I and Col III)-positive area in the healing wound skin after TiOx@C treatment. Collagen type I is the major component of the ECM in skin and plays crucial role in the early inflammatory and proliferative phases of wound healing, which provides tensile strength to the wound and promotes tissue reconstruction. Col III, on the other hand, gives the wound elasticity and flexibility61. Col I has a higher tensile strength and will form more resilient scar tissue, while Col III allows for better wound recovery and is less likely to form scar. It can be found that Col III is more positive in the treatment group than in the control group, which indicates that TiOx@C with promoting healing effect could achieve optimal tissue repair and minimize scar formation, possibly attributed to its porous fiber-like carbon substrate with good electrical conductivity.

Encouraged by the great antimicrobial and pro-wound healing properties of TiOx@C in wound-infected mice, we then further evaluated the long-term toxicity of TiOx@C in healthy mice to assess its potential application as an antibiotic alternative. The assessment of hematological and blood biochemical markers for mice on day 14 showed no significant abnormalities or deleterious effects in TiOx@C-treated mice, suggesting that TiOx@C has insignificant toxicity and can be used for further in vivo experiments (Figs. S27a, b, Supplementary information). Furthermore, histological analyzes of major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lungs and kidneys) were performed. H&E staining images show negligible histological abnormalities or pathological changes in TiOx@C -treated mice compared to normal healthy mice (Figs. S27c, Supplementary information). In conclusion, TiOx@C exhibits favorable biosafety and possesses the potential to be applied as an effective nanoagent for the synergistic treatment of bacterial infections and wound healing.