Comparable distribution of immune cell populations in bronchoalveolar compartments from people living with HIV and healthy controls

To characterize the immune cells in the bronchoalveolar compartments of PLWH on ART and HIV-uninfected persons and to study their responses to Mtb infection, we enrolled two groups of study participants: PLWH on ART and HIV-uninfected healthy controls (HC). We collected bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples from PLWH on ART (n = 7) and HC (n = 9). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of study participants enrolled in the study. All PLWH were stable on ART with median CD4 counts of 493 cells/ul; interquartile range (IQR) (271–833); and all the participants had undetectable HIV viral load. BAL cells isolated from the BALF of participants from HC and PLWH on ART were used for immunophenotyping at baseline and infected with Mtb for single-cell transcriptomics (10X Genomics) and analysis of immune function by high-dimensional flow cytometry (Fig. 1A).

A Overview of experimental methodology. Briefly, BAL fluid was collected through bronchoscopy from HCs (n = 9) and PLWH (n = 7). BAL fluid was processed to obtain BAL cells, portion of which were used for immunophenotyping and intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) at baseline. Parallelly, BAL cells from HC and PLWH were infected with Mtb for 4 h and processed further for flow cytometry, ICS, and ScRNAseq. Created in BioRender. Bajpai, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/u96g032 (B) Distribution of immune cells in BAL identified through flow cytometry. Each bar represents one subject, and color shows different cell types. C Boxplot shows distribution of major cell types in the BAL between HC (n = 9) and PLWH (n = 7) identified through immunophenotyping. Individuals are represented as dots. The following parameters are shown: minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and maximum. Two-sided Student’s t-test was used to compare difference between sample means. ns; p value > 0.05. A was generated using BioRender.

To determine the composition of immune cell populations in BAL cells from HC and PLWH on ART, we performed comprehensive immunophenotyping using multiparameter flow cytometry (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 1). Alveolar macrophages (AMs) were the predominant immune cells in BAL cells from both groups, with a median of 78.6% (IQR: 67.2–90.0) in HC and 75.1% (IQR: 61.5–76.1) in PLWH, as expected (Supplementary Table 1). Other notable immune cell types included CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, monocytes, neutrophils, and epithelial cells; however, we did not observe any significant differences in the frequencies of these cell types between the two groups (Fig. 1C).

Single cell transcriptional profiling reveals global transcriptional changes across multiple cell types in response to Mtb

We sought to investigate the transcriptional responses of AMs and other BAL cells from PLWH and HCs to ex vivo infection with Mtb by carrying out single cell transcriptomic profiling (scRNA-seq;10X Genomics) at baseline (no infection) and after infection with Mtb H37Rv at an MOI of 2 for 4 h. After this time, cells were collected for bacterial enumeration and processing for ScRNA-seq. After plating intracellular Mtb, colony forming units (CFUs) were 1 × 106 (IQR: 0.5 × 106–1.37 × 106) in HC and 1.25 × 106 (IQR: 0.4 × 106–2.12 × 106) CFU/ml in PLWH, demonstrating that bacterial loads were comparable between the two groups. After alignment and preprocessing of the ScRNAseq data, we obtained an average of 3362 cells per sample, yielding a total of 57,160 cells. Upon mapping sequences to the Human Primary Cell Atlas reference dataset, we identified 12 distinct cell populations (Supplementary Fig. S2A): alveolar macrophages (MACRO+, CD68 +, FCGR3A+), monocyte derived macrophages (MACRO+, SIGLEC5−), neutrophils (S100A8 +, S100A9+), dendritic cells (CD1C +, CD207 +), monocytes (LYZ +), CD4 T cells (CD3D +, CD3E +, CD4 +), CD8 T cells (CD3D+, CD3E +, CD8A+), gamma delta T cells (CD3E +, CD3G +), T-regulatory cells (FOXP3 +), B cells (MA4A1 +, CD79A +), NK cells (GNLY +, PRF1 +) and epithelial cells (MUC5AC +). Cell types projected in two dimensions using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) are shown in Fig. 2A. Cell populations were further validated using canonical gene expression markers (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Overall, the cell types identified by scRNA-seq are consistent with our flow cytometry data (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 2B). Notably, after Mtb infection, in AMs from both HC and PLWH, we identified AM clusters that were distinct from the AM clusters in the Mtb-uninfected groups (Supplementary Fig 2C), demonstrating that Mtb infection leads to significant changes within the AM compartment.

A Concatenated UMAP of HC (n = 5), PLWH (n = 3), HC + Mtb (n = 5), and PLWH + Mtb (n = 4) shows the annotated cell types in the BAL cells. B Heatmap of top 10 variable genes per group. Color represents the Z-scores (row normalization) of the average expression of each gene for each group and cell type. Genes with high expression are shown in red and low expression in blue. Genes in each row were clustered using hierarchal clustering by farthest neighbor method. C Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the HC + Mtb compared to HC and PLWH + Mtb compared to PLWH. D Manhattan plot shows the pathways enriched in unique DEGs in HC + Mtb vs HC (green), unique DEGs in PLWH + Mtb vs PLWH (orange), and common DEGs between HC + Mtb vs HC and PLWH + Mtb vs PLWH (violet). Y-axis shows the FDR corrected p value obtained from the pathway enrichment analysis, and size of each bubble shows the count of genes that overlapped with reference pathway. P value was estimated using overrepresentation analysis in R package enrichR.

We next sought to identify genes whose expression varied significantly across the four groups (HC, PLWH, HC + Mtb, and PLWH + Mtb) and across the different cell types. A heatmap of the top differentially expressed genes indicates that the greatest differences between PLWH and HC occurred following Mtb infection, across multiple cell types (Fig. 2B). We then performed differential gene expression analysis to identify genes that were upregulated or downregulated in PLWH versus HC, in the presence or absence of Mtb, across all cell subsets. Using cutoff criteria of foldchange greater than 1.3 or less than −1.3 and adjusted p value < 0.05, we found a total of 1105 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in HC + Mtb compared to HC and 902 DEGs in PLWH + Mtb compared to PLWH group (Fig. 2C). Of the total DEGs, 710 were common between the HC + Mtb and PLWH + Mtb, while 395 and 192 genes were unique to HC + Mtb and PLWH + Mtb respectively (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. 2D). Pathway enrichment analysis of common and unique DEGs across all cell types indicated that while both HC and PLWH showed positive enrichment of multiple pathways upon Mtb infection, including TNF signaling via NFκB, and IL-1 signaling, enrichment of many of these these pathways were lower in PLWH + Mtb compared to HC + Mtb (Fig. 2D).

Altered alveolar macrophage and T cells profiles in PLWH on ART following Mtb infection

To further evaluate how Mtb infection impacts the transcriptional profiles of the main innate and adaptive cell types from PLWH and HC, we compared the DEGs between PLWH and HC in the following major cell types: AMs, monocytes, CD4 T, CD8 T, and NK cells, at both baseline and after Mtb infection. Using cutoff criteria of foldchange ≥ 1.3 or ≤−1.3 and adjusted p value < 0.05, we found 50 genes to be upregulated, and 45 genes downregulated in AMs from PLWH compared to HC at baseline as shown in the alluvial plots in Fig. 3A. Upon Mtb infection, the number of DEGs in AMs increased to 103 upregulated and 206 downregulated (Fig. 3A). Similar trends were observed in CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells and NK cells (Fig. 3A). Other cell subsets either showed minimal changes in response to Mtb (DCs and monocytes) or had no significant DEGs (γδT, Treg, Fig. 3A). Focusing on the DEGs post-Mtb infection, we found that AMs from PLWH downregulated multiple cytokine and chemokine genes relative to HC, such as IL-6, TNF, IL1A, IL23A, IL1B, CCL4/5, CXCL1/3/8 and the antioxidant SOD2, suggesting that AMs from PLWH on ART are unable to mount robust pro-inflammatory and antimicrobial responses to Mtb (Fig. 3B). Moreover, CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells and NKs cells from PLWH + Mtb showed signatures of immune activation and heightened inflammation (HLA-DRA/DRB, TNF, CCL4) relative to HC + Mtb and downregulation of GZMA, GZMB, and GNLY which encode granzyme A, B and granulysin, respectively, suggesting blunted cytotoxic T cell responses in PLWH (Fig. 3B).

A Alluvial plot shows the change in number of differentially expressed genes between PLWH vs HC and PLWH + Mtb vs HC + Mtb. Up-regulated genes are shown in red, while downregulated genes are shown in blue. Only the cell types with significant number of DEGs are shown. B MA-plot shows the gene expression profile of PLWH + Mtb vs HC + Mtb in major cell types. X-axis shows the normalized log2 mean expression of each gene, and y-axis shows the log2 foldchange. Up-regulated genes are shown in red, while downregulated genes are shown in blue. C Bubble plot shows the enriched pathways between PLWH + Mtb and HC + Mtb obtained from gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). Up-regulated pathways in PLWH + Mtb vs HC + Mtb are shown in red, while downregulated pathways are shown in blue. The size of the bubble represents the size of the reference pathway (i.e., number of genes which compose that pathway).

To identify pathways that differ between innate and adaptive immune cells from PLWH + Mtb versus HC + Mtb, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using Hallmark and Reactome reference datasets. Host pathways corresponding to proinflammatory cytokine signaling, such as TNF, IL-1, IL-6, IFN-α, and IFN-γ, were significantly lower in AMs, DCs, and monocytes from PLWH + Mtb compared to HC + Mtb (Fig. 3C) following Mtb infection, along with diminished IL-4/13 and IL-10. These data suggest that in contrast to HC, which successfully mounts a robust and balanced innate inflammatory response, PLWH are defective in responding to Mtb infection. This is supported by the lack of upregulation of glycolysis in PLWH, where genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), electron transport, and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle metabolism were enriched in innate cell subsets (Fig. 3C). In contrast, OXPHOS and TCA metabolic genes were lower in CD4 and CD8 T cells from PLWH along with lower IFN-α and IFN-γ signaling (Fig. 3C), suggesting poorly functional T cells in lung compartments of PLWH.

T cell subsets in the airways of PLWH reflect heightened immune activation and dysregulation

We characterized the T cell subsets present in the bronchoalveolar compartments of PLWH and HC at baseline and assessed changes following infection with Mtb. We identified multiple subsets of CD4 and CD8 T cells as shown in the concatenated UMAP plot of all 4 groups (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 3A). Figure 4B shows that uninfected BAL cells from PLWH and HC both harbored similar CD4 T central memory (TCM), CD4 and CD8 T effector memory (TEM) and Treg subsets. However, Mtb exposure led to shifts in the TCM and TEM populations in each group, with a distinct CD4 TEM2 cluster in HC that was absent in PLWH, and a CD8 TEM2 cluster in PLWH that was absent in HC (Fig. 4A). These population shifts were not associated with cell death as cell viability and percentage of mitochondrial content were observed to be similar before and after Mtb infection (Supplementary Fig. 3B, C). Pseudotime and GSEA analysis suggest that upon Mtb infection, resting CD4 and CD8 T cells in HC likely differentiate into effector memory CD4 T cells with an antimicrobial gene expression profile (CD4TEM2), and CD8 T cells with cytotoxic profiles (CD8 TEM1), including a granzyme K-expressing CD8 T cell subset (CD8 TEM GZK+) (Fig. 4C). Importantly, these effector memory CD4 and CD8 T cell subsets are not present in PLWH; instead, Mtb infection leads to differentiation into a unique subset of effector memory CD8 T cells (CD8 TEM2), and a small IFN-γ-expressing CD8 effector memory subcluster, both of which are absent in HC (Fig. 4C).

A Concatenated UMAP of HC (n = 5), PLWH (n = 3), HC + Mtb (n = 5), and PLWH + Mtb (n = 4) shows various T-cell subsets annotated using canonical reference markers. B UMAP of T-cell subsets identified in HC, PLWH, HC + Mtb, and PLWH + Mtb groups. C Pseudotime trajectory of T cell subsets inferred using Monocle 3. Cells were colored by pseudotime. D MA-plot shows the gene expression profile of PLWH + Mtb vs HC + Mtb in T cell subsets. X-axis shows the normalized log2 mean expression of each gene, and y-axis shows the log2 foldchange. Up-regulated genes are shown in red, while downregulated genes are shown in blue. Only the subsets with enough DEGs are shown. E Bubble plot shows the enriched pathways between PLWH + Mtb and HC + Mtb obtained from gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) in various T cell subsets. Up-regulated pathways in PLWH + Mtb vs HC + Mtb are shown in red, while downregulated pathways are shown in blue. The size of the bubble represents the −log10 p value. The larger the size of the bubble, lower the p value. P value and enrichment score are obtained from GSEA analysis using R package fgsea.

To further understand the functional capacity of these T cell subsets, we analyzed the DEGs that differed the most between PLWH + Mtb and HC + Mtb. Figure 4D, E shows that multiple genes within the effector memory CD4 TEM2 and CD8 TEM1 subsets were downregulated in PLWH compared to HC, and GSEA shows that these downregulated genes corresponded to IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IL-15, IL-17, IL-21 and TNFR1 signaling pathways, suggesting substantially reduced CD4 and CD8 T cell functionality in PLWH. Further, effector memory CD8 TEM2 subsets present in PLWH significantly upregulated immune activation genes (e.g., HLADRA/B1) and were enriched for IL-10 signaling pathways, along with reduced cytokine signaling pathways (Fig. 4D, E). Finally, Tregs from PLWH + Mtb also displayed gene signatures of hyper immune activation and were significantly enriched for signaling pathways corresponding to anti-inflammatory IL-10 and IL-4/IL-13 cytokine signaling, suggesting that Tregs, preferentially induced in PLWH, may contribute to skewing away from a proinflammatory milieu and towards an immunosuppressive or anti-inflammatory lung microenvironment (Fig. 4D, E).

Cell-cell communication networks reflect divergent immune responses to Mtb in PLWH versus HC

To identify cell-cell communication networks operant in PLWH versus HC following Mtb infection, we used CellChat, which uses a comprehensive curated database of ligand-receptor interactions and network analysis to predict communication probabilities for different pathways from single cell transcriptomics data. We calculated the relative flow of information for each pathway within the database by aggregating communication probabilities across all cell types for each pathway. A higher relative information flow score indicates increased communication between cell subsets. CellChat predicted significant induction of IL-6, IL-1, TNF signaling networks, CD86 costimulatory, and MHC-I signaling pathways in HC + Mtb (Fig. 5A). However, these interaction networks were either absent or significantly lower in PLWH + Mtb. Notably, further analysis predicted crosstalk primarily between AMs and lymphocytes in HC infected with Mtb (Fig. 5B) within costimulatory and TNFSF-TNFRSF member signaling networks: TNFRSF1A/1B (TNF), TNFRSF13 (APRIL), and TNFRSF13B (BAFF). The TNF signaling network, which involves interaction between TNF and TNFRSF1A/1B, was predicted to be the strongest with the highest number of edges (represented by thicker lines) connecting AMs to CD4 T cells as well as other T cell and innate cell types (Fig. 5B, top panel). Interestingly, AMs were also central to the anti-inflammatory cell-cell communication networks that dominated in PLWH + Mtb compared to HC + Mtb, such as CD39 and LIGHT (TNFRSF14), as shown in Fig. 5A, B (bottom panel). The predominance of LIGHT in PLWH over the more proinflammatory TNF, APRIL, and BAFF signaling networks seen in HC following Mtb infection suggests that TNFSF networks are dysregulated in PLWH and likely hinder effective host defense against Mtb infection.

A Figure shows the strength of cell-cell communication of significant pathways in HC + Mtb and PLWH + Mtb groups. X-axis shows the relative flow of information obtained from the sum of cumulative probabilities between interacting cell types and then scaled from 0 to 1. Higher value indicated higher ligand-receptor interaction between cells in each pathway. B Cell-cell communication network shows the putative interactions between ligand and receptor pairs. The arrow indicates the directionality of interaction, and the width of the edge indicates the strength of communication.

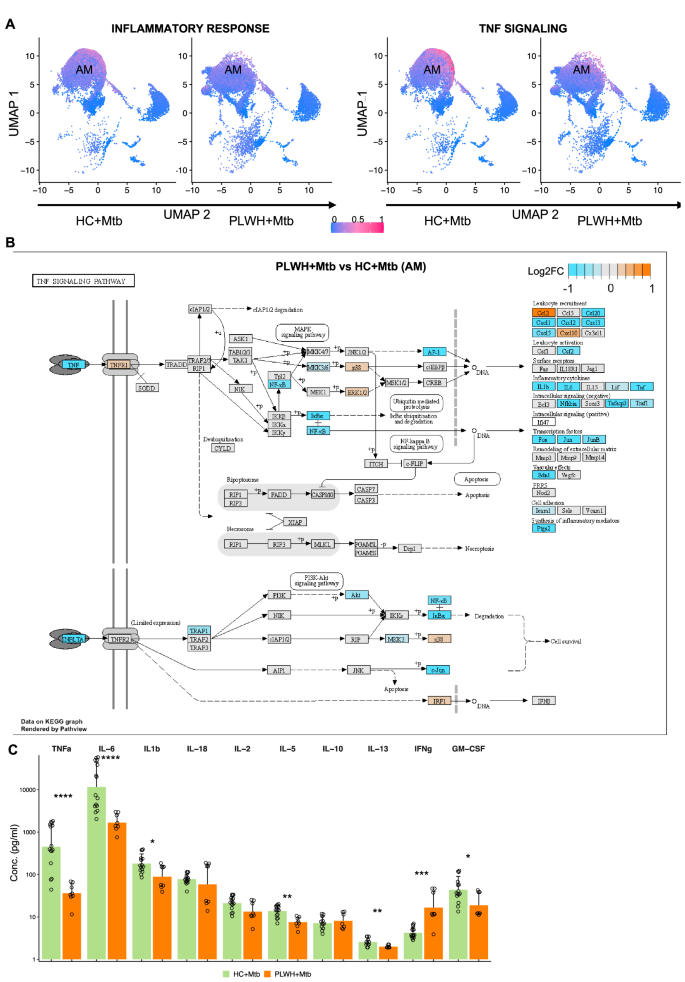

Impaired TNF-TNFR signaling networks in alveolar macrophages from PLWH

Since our data highlighted defective inflammatory responses to Mtb in PLWH, in particular, TNFSF-TNFRSF signaling pathways, we sought to infer the strength of inflammatory activity across each immune cell type present in BAL. We calculated pathway scores for inflammatory response pathways that were found to be downregulated in PLWH + Mtb compared to HC + Mtb (Fig. 6A, left). The pathway activity score for combined inflammatory response pathways was significantly lower in PLWH + Mtb compared with HC + Mtb. Similar results were seen for the TNF-TNFR signaling pathway (Fig. 6A, right), with AMs being the dominant contributors to inflammatory and TNF signaling pathways (Fig. 6A). To assess the TNF-TNFR signaling pathways more closely in AMs from PLWH and HC, we overlayed the fold changes of all genes involved in the TNF signaling pathway obtained from the KEGG database. Figure 6B shows that several genes within these pathways were lower in PLWH + Mtb compared to HC + Mtb. These genes include NFKB, IKBA, AKT, MKK3, TRAF1, and JUN. We also observed significantly lower expression of genes downstream of TNFR1 that encode IL-6, IL-1β, chemokines involved in leukocyte recruitment (CCL20, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, and CXCL5), transcription factors (Ap1, c-Fos, c-Jun), inflammatory mediators (PtgS2) and negative regulators of intracellular signaling (Tnfaip3). In contrast, CCL2, associated with chronic immune activation in PLWH on ART, was upregulated (Fig. 6C). To validate these data at the protein level, we quantified the levels of multiple cytokines from the supernatants of Mtb-infected BLCs from PLWH and HC using multiplex ELISAs. Several proinflammatory cytokines were significantly higher in HC compared to PLWH, including TNF, IL-6, IL-1β, and GM-CSF (Fig. 6C). Overall, these data show that AMs from PLWH are defective in mounting TNF and downstream signaling pathways.

A UMAP shows the pathway enrichment score for inflammatory pathway (left panel) and TNF signaling pathway (right panel). Pathway enrichment score for each cell ranges from low (blue) to high (pink). B Pathway analysis of KEGG TNF signaling pathway using pathview. Genes are colored by log2 fold change between PLWH + Mtb vs HC + Mtb. C Concentration of inflammatory cytokines quantified using Luminex technology in HC + Mtb (n = 6) and PLWH + Mtb (n = 3). X-axis shows the various cytokines, and y-axis shows the concentration. Each dot represents individual sample, and the bar shows the mean. Data is represented as mean ± SEM. Difference in the means was estimated using two-sided Wilcoxon non-parametric t-test. ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

Impaired induction of M1-like AMs and TNF signaling in PLWH on ART following Mtb infection

To further dissect AM functions in response to Mtb in HC versus PLWH, we asked which specific AM subpopulations contribute to the differential inflammatory responses in the two groups. Using Seurat clustering, we identified 5 distinct transcriptional subclusters of AMs (AM1 to AM5; Fig. 7A–C). Of these, subclusters AM2, AM3, and AM4 were prominent after Mtb infection in both HC and PLWH (Fig. 7B), while the AM1 cluster, which displayed a resting cell signature, was present mostly at baseline in both groups. The AM5 subcluster, which co-expressed lymphocyte markers, was excluded from subsequent analyzes. Interestingly, the AM3 subcluster displayed an activated, strongly proinflammatory M1-like signature which included NFKBIA, IL1B, IL1RN, IL-6, TNF, chemokine genes (CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL8, CCL3, CCL4, CCL20) and the antimicrobial gene superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2; Fig. 7C–E). The AM2 subcluster also shared many of these proinflammatory genes, but at lower levels than AM3, and had poor upregulation of NFκB signaling, suggesting a less-activated intermediate AM phenotype (Fig. 7D). The AM4 subcluster, which was enriched in PLWH compared to HC post Mtb infection, displayed a unique transcriptional signature that lacked expression of proinflammatory genes but expressed genes that contribute to anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory responses (BCL2, AKT3, SMAD2; Fig. 7D). A GSEA plot of the four subsets (Fig. 7E) confirms the distinct gene expression patterns for each AM subset: AM1 exhibit a quiescent metabolic state, the M1-like proinflammatory AM3 subset show potent TNF signaling via NFκB activation, and AM4 subsets upregulate TGF-β family signaling and cholesterol storage pathways.

A Concatenated UMAP of HC, PLWH, HC + Mtb, and PLWH + Mtb shows various AM subsets identified using Seurat clusters. B UMAP shows AM subsets in HC, PLWH, HC + Mtb, and PLWH + Mtb groups. C Transcriptional profile of top genes representative of each cluster is shown as heat map. Normalized expression values are plotted ranging from low (pink) to high expression (yellow). Notable genes from AM3 and AM4 clusters are labeled at the bottom. D Violin plot shows the normalized expression of genes representative of each AM subset. E Bubble plot shows the significantly enriched pathways each AM subset obtained from gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) in various T cell subsets. Up-regulated pathways in each AM subset compared to other AM subsets are shown in red, while downregulated pathways are shown in blue. The size of the bubble represents the size of the reference pathway.

To better understand the relationship between the different AM subpopulations that develop following Mtb infection in HC and PLWH, we conducted pseudotime analysis to infer the pseudo-temporal trajectories of the AM subsets and their underlying gene expression programs. Pseudotime analysis indicates that the AM1 subset is present mainly at baseline in both groups, while the other subsets arose sequentially from AM1 following infection (Fig. 8A, B). Interestingly, comparison of PLWH + Mtb versus HC + Mtb groups by GSEA across the four AM subsets reveals that deficits in the AM3 subset proinflammatory functions are primarily responsible for the inability to upregulate inflammatory cytokine-mediated signaling pathways in PLWH following Mtb infection. AM3 subsets present in PLWH + Mtb have prominent defects in TNF signaling pathways (Fig. 8C) and have significantly lower expression of key proinflammatory genes (Fig. 8D). Pseudotime analysis comparing TNF signaling cascades across AM1-AM4 subsets in HC + Mtb versus PLWH + Mtb shows a striking pattern of AM3 subsets acquiring TNF-TNFR signaling following Mtb infection in HC (Fig. 8E). In contrast, AM3 subsets from PLWH do not acquire these genes upon stimulation with Mtb and show impaired TNF signaling via NFκB. Thus, AM3 subsets from PLWH are significantly impaired in their activation status and capacity to induce TNF and other proinflammatory cytokine responses necessary for controlling Mtb infection. Taken together, these results demonstrate that AMs from PLWH are impaired in their capacity to develop into fully activated M1-like proinflammatory effector cells that are necessary for mounting effective immune responses to Mtb.

A Concatenated UMAP of HC, PLWH, HC + Mtb, and PLWH + Mtb shows AM subsets color coded by pseudotime. The cells are color-coded from early (violet) to later (yellow) timepoint in pseudotime. B UMAP shows the AM subsets in HC + Mtb and PLWH + Mtb colored by pseudotime. C Bubble plot shows the enriched pathways between PLWH + Mtb and HC + Mtb in different AM subsets obtained from gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). Up-regulated pathways are shown in red, while downregulated pathways are shown in blue. The size of the bubble represents the size of the reference pathway. D Violin plot shows the distribution of top DEGs in PLWH + Mtb vs HC + Mtb in AM3 subset. E Heatmap shows the expression of differentially expressed genes in the TNF signaling pathway across the pseudo-space. Each row shows the gene clustered hierarchically in HC + Mtb and PLWH + Mtb groups. The bar at the top indicates the estimated annotation of cells. F Cell-cell communication network shows the putative interactions between ligand and receptor pairs in HC + Mtb and PLWH + Mtb. The arrow indicates the directionality of interaction, and the width of the edge indicates the strength of communication.

Defects in crosstalk between M1-like alveolar macrophages and airway T cells in PLWH on ART

We next asked whether cell-cell communication networks between specific AM and T cell subsets were altered in PLWH compared to HC following Mtb infection. CellChat analyzes highlighted key AM-T cell interaction networks that were significantly enriched in HC + Mtb versus PLWH + Mtb. Specific pathways of interest are represented in Fig. 8F, showing crosstalk between AM and T cell subsets within each pathway. Cell-cell communication network analysis shows that the activated M1-like AM3 subset is the major immune cell predicted to engage with T cells via TNF-TNFRSF1A/1B, Lck-CD8A/B1, CXCL16-CXCR3, CD86-CTLA4 and PGE2-PTGES interactions (Fig. 8F and Supplementary Fig. 4). The AM3 subset shows strong interactions with CD4 effector memory T cells in HC (CD4 TEM2), in the context of pathways related to proinflammatory responses, T cell activation and immune cell recruitment. However, these interactions are significantly diminished or absent in PLWH, where interactions with chronically immune-activated CD8 TEM subsets and Tregs dominate. Moreover, PLWH harbor interactions between anti-inflammatory AM4 and T cells within the CD96-PVR axis, which is involved in promoting immunosuppression in many pathological conditions, such as tumors (Fig. 8F). These results suggest that critical AM interaction networks required for effective immunity against Mtb in lung compartments are absent in PLWH on ART.

Alveolar macrophages from PLWH exhibit an anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive profile

To validate our bioinformatics predictions at the cellular level, we performed flow cytometry analysis and intracellular cytokine staining on BAL cells after 4 h and 24 h of ex vivo Mtb infection using a panel that included phenotypic and functional macrophage markers. We observed that frequencies of TNF secreting AMs were lower in PLWH compared to HC after 4 h of Mtb infection. Additionally, we found that even after 24 h of Mtb infection, TNF secreting AMs did not recover and continued to remain at relatively low levels in PLWH compared to HC (Fig. 9A, B and Supplementary Fig 5A). Responses to stimulation with TLR ligands were, however, comparable in both groups (Supplementary Fig. 5B–E). The frequencies of IL-6+, HLA-DR+, CD40+ and CD80+ were also observed to be relative lower in PLWH compared to HC at both 4 h and 24 h after Mtb infection, indicating potential impaired activation and costimulatory capacity (Fig. 9B). To further understand differences between the profiles of AMs in HC versus PLWH, we performed high dimensional analysis of the flow cytometry data using a combination of phenotypic and functional markers from all timepoints. TNF, IL-6, CD38, HLA-DR, IL-10, and CD200R were used for dimensionality reduction using UMAP and then clustered using ClusterExplorer. We identified three distinct subsets of AMs consisting of one smaller population, Pop0, and two larger populations, Pop1 and Pop2 (Fig. 9C, E). Pop0 was IL-6+, TNF+ but negative for activation markers CD38 and HLA-DR and negative for IL-10 and the immunosuppressive receptor CD200R. Pop1, annotated as proinflammatory and activated (IL-6+, TNF+, CD38+, HLADR+, IL-10+, CD200Rlow; Fig. 9D), emerged as the major population in HCs (Fig. 9E, F top panel). Pop2 expressed both the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 and high levels of the immunosuppressive receptor CD200R but was negative for TNF and IL-6 (IL-6neg, TNFneg, CD38+, IL-10+ and CD200R+, Fig. 9D) and was the dominant population in PLWH (Fig. 9E, F). The enrichment of TNF and IL-6 expression in Pop1 from HC versus the enrichment of IL-10 and CD200R in Pop2 from PLWH is further highlighted in Fig. 9F. We next quantified Pop1 and Pop2 subsets in uninfected and Mtb-infected samples from HC and PLWH groups. Fig. 9G, H show that frequencies of IL-10+CD200R+ AMs were significantly higher in PLWH compared to HCs both at baseline and after Mtb infection. Further, we found that TNFneg AMs from PLWH expressed both IL-10 and CD200R, whereas HCs had very low frequencies of TNFneg IL-10+CD200R+ AMs. In contrast, AMs that were positive for TNF+ did not express IL-10 and CD200R.

A Representative flow cytometry plots show the frequency of TNF+ AMs in HC and PLWH at baseline and at 4 h and 24 h after infection. B Frequency of AMs positive for inflammatory cytokine and activation marker of HC + UN (n = 5), PLWH + UN (n = 4), HC + Mtb 4 h (n = 4), PLWH + Mtb 4 h (n = 3), HC + Mtb 24 h (n = 6) and PLWH + Mtb 24 h (n = 3) are shown. Data is represented as median ± SEM. The difference in the means was calculated using two-sided Wilcoxon non-parametric test. None of the groups showed significant differences. C UMAP projection shows the combined events obtained by down sampling to select 12,000 AM events from each sample (n = 3 for both HC and PLWH). The clustering was performed using FlowSOM/ClusterExplorer. D Heatmap shows the relative MFI of markers used for UMAP and clustering in (C). E Percentage of each population of the total cells. F UMAP of HC and PLWH are shown on the left panel. The right panel shows the visualization 2D plots from the UMAP. The contribution of each cluster for the expression of either TNF/IL-6 or IL-10/CD200R is shown. G Gating strategy of CD200R+IL10+ AMs (top panel), TNFneg CD200R+IL10+ AMs (bottom panel), and TNF+CD200RnegIL10neg AMs (bottom panel) in HC and PLWH with and without Mtb infection are shown. H Frequency of CD200R+IL10+ AMs (left panel), TNFneg CD200R+IL10+ AMs (middle panel), and TNF+CD200RnegIL10neg AMs (right panel) in HC and PLWH with and without Mtb infection are shown. Uninfected groups are labeled as UN (HC, n = 6; PLWH, n = 3), and Mtb group includes samples after 4 h or 24 h post-infection (HC, n = 11; PLWH, n = 6). Data is represented as median ± SEM. Barplot shows the median, and each dot represents individual sample. Statistical difference between UN and Mtb groups was estimated using two-sided Wilcoxson non-parametric test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ns, not significant.

In summary, our data indicate that PLWH on ART are unable to mount effective TNF-TNFR signaling networks and related proinflammatory responses to Mtb in their airways. Further, we provide evidence for impaired crosstalk between AMs and T cells in PLWH, which together suggest aberrant immunity to Mtb infection in lung compartments. Moreover, the presence of AM subsets expressing IL-10 and CD200R in PLWH following Mtb infection suggest immunoregulatory functions that may suppress proinflammatory responses and hinder effective immunity. Developing therapies that target these deficits has potential to improve outcomes for PLWH on ART. Moreover, our studies provide new insights that may be applicable to other opportunistic respiratory infections that affect PLWH on ART.