Stevenage Museum was closed after I visited. However the church above it was open. St Andrew & St George, an ethereal Modernist concrete construction with an enormous stained-glass window accomplished in 1966, the yr England gained the World Cup, was internet hosting a pantry to assist locals out with a free cup of tea and a meal. The ambiance was welcoming however restrained, just a few individuals chatting, an older man consuming a sandwich on his personal, perched on a plywood pew.

Stevenage was as soon as the longer term, a mannequin for a brand new way of life. Its Modernism, principally low-rise, purposeful and compact, seems nearly quaint these days: an expression of a paternalistic period of state-sponsored constructing and council housing. Within the Fifties, architects and urbanists got here from everywhere in the world to check the daring experiment that it embodied. Now it has change into a sort of Modernist heritage, a model of a future that may have been.

Located 27 miles north of London, Stevenage was the pioneering manifestation of the New Cities Act handed by parliament in 1946. It will be quickly adopted by Basildon and Bracknell, Corby and Crawley and, later, Runcorn, Ravenscraig, Cumbernauld and Telford — some profitable, others rather less so. London had been devastated by bombing within the second world struggle, with greater than one million dwellings broken or destroyed, and the energetic new Labour authorities wasted no time in planning for a future dispersal of residents to past the war-torn, ragged and nonetheless industrial capital.

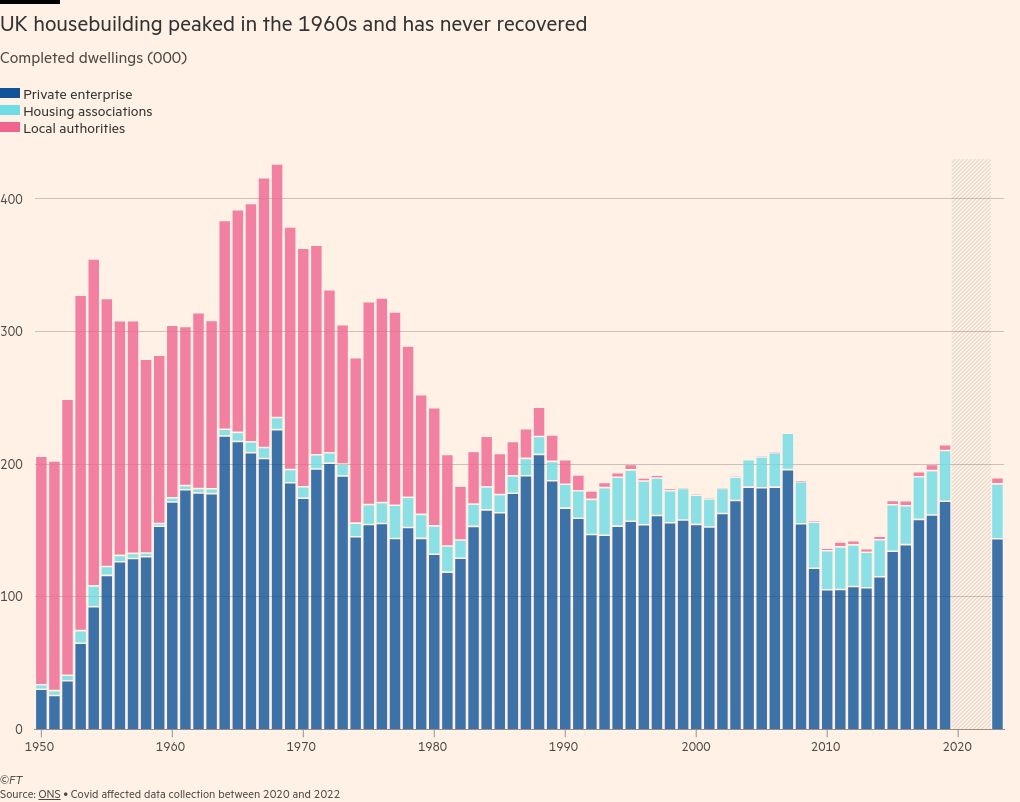

Now new cities are again as one other new Labour authorities touts them as a part of the answer to the UK’s housing disaster. The final authorities’s formidable housebuilding targets had been stymied by its personal rural and suburban MPs, frightened of their constituents’ ire. Nimbyism has been a robust drive in politics. Nearly everybody agrees on the necessity to construct extra homes — simply not close to the place they dwell.

The brand new authorities’s legislative programme, set out within the King’s Speech this summer season, steered that communities would get a say on “how, not if” new properties are to be constructed. If the federal government is to confront the difficulty, new cities comparable to Stevenage should absolutely be again on the agenda. However are they, in the end, factor?

Simply earlier than the election, the now deputy prime minister Angela Rayner revealed new visions of immediately’s cities of the longer term, renderings apparently created utilizing AI that confirmed mistily nostalgic Edwardian-style red-brick mansion blocks, tree-lined streets and pavement cafés. Rayner, whose ministerial transient covers housing, steered that solely “enticing” properties can be constructed. Who, in any case, objects to “enticing” housing? David Milner, director of the foyer group Create Streets (accountable for these photographs) writes: “We consider stunning and sustainable design helps to spice up housing supply by profitable over residents.”

The quasi-religious sanctity of the greenbelt is sensibly being questioned, and areas recognized as ‘gray belt’ may very well be freed up

The historicism of these machine hallucinations is a revealing echo of lingering British anxieties over fashion and modernity. The nation (or at the very least its builders) proved somewhat immune to Modernism within the early twentieth century, its public buildings veering between Neo-Georgian or Artwork Deco and its housing dominated by Artsy-Craftsy, half-timbered semis with the occasional stab at a extra “continental” Modernism.

Stevenage represented a clear break. At its coronary heart was the UK’s first Modernist city centre. Its design stays largely intact immediately; strolling by way of its streets, with their canopies, benches, inexperienced areas and play areas, provides somewhat blast of postwar city utopianism. The pedestrianised streets (additionally the nation’s first) is perhaps somewhat shabbier than in mid-century images; there are many charity outlets, slot-machine joints and some huge empty hulks (a defunct BHS and Poundland) however the centre continues to be energetic.

One focus is an summary, sculptural clock tower, a ghost of that almost all municipal centrepiece of the Victorian metropolis, right here remodeled right into a Modernist monument to the place itself: a ceramic map of the brand new city on one facet, on one other a portrait of Lewis Silkin, the minister accountable for establishing new cities. When Silkin arrived within the small outdated city of Stevenage subsequent to the location in 1946 he was confronted by protests concerning the 10,000 new council properties within the Hertfordshire countryside. “It’s no good you jeering,” he shouted over the group. “It’s going to be finished.”

New developments provoke enormous resistance and the UK’s planning system is immensely amenable to objections. It follows that the federal government’s plans are closely skewed in direction of reform of the planning system. The quasi-religious sanctity of the greenbelt is sensibly being questioned, and areas recognized as “gray belt” (which could include automobile parks, derelict buildings, transport sidings, agricultural buildings or petrol stations) may very well be freed up. Evaluation by property brokers Knight Frank suggests such websites may accommodate as much as 200,000 properties, principally within the south and significantly the areas surrounding London.

New cities, although, are one thing else. Though the federal government is consulting on potential areas, one of the crucial apparent websites is the Oxford-Cambridge hall, a long-mooted plan for a “knowledge-intensive arc” that might have, roughly at its centre, the final and most profitable of the UK’s new cities: Milton Keynes. This band of growth might accommodate as much as one million new properties and be deliberate round a revived Oxford-to-Cambridge rail line. One upside is employment and desirability — tech, biosciences and pharma are all nicely rooted right here. The hazard is proximity to London and the college cities — new cities might change into dreary dormitory suburbs with little lifetime of their very own.

However regardless of the dangers, the necessity is there. In response to a report by Schroders, the typical home now prices 9 instances common earnings; in 1999 it was half that. If Britain is to deal with itself sooner or later, one thing should give.

Again on the church in Stevenage, I talked to rector Karen Mitchell. She launched me to Jan and Mike Wilson who, she mentioned, had been the “actual locals”.

“I’d been married for a yr and I acquired a council home right here after being on the ready checklist for 2 weeks,” Mike advised me. “When Stevenage was constructed, it was all council homes. All the things.”

Jan provides: “Now our granddaughter has been on the ready checklist for years. And it’s hopeless, there’s at all times going to be somebody extra needy.” This isn’t simply notion. There are presently 1.3mn households on native authority ready lists.

Not like the equally cash-strapped postwar Labour authorities — which facilitated an enormous programme of slum clearance, prefabrication and council housing (together with founding the NHS and the welfare state) — this authorities seems to recommend that the brand new housing might be delivered largely by the personal sector.

What do we would like cities to be now? These twee photos of Edwardian-style streets recommend a sure timidity

Is that this actually the very best route? There may be little incentive for builders to flood the market with new properties and danger reducing costs, whereas enormous public funding is required in creating a brand new city. The postwar new cities had been constructed by growth companies, government-established our bodies that oversaw their planning and infrastructure. However this sort of large-scale planning has light away as native authorities have been successively starved of money within the post-austerity years. The 300 further planners the federal government has promised will barely make a dent.

In 1946, as in 2024, a Labour authorities needed to introduce laws to create new cities. The query is whether or not we nonetheless have the identical ambition and confidence. Stevenage was a decided assertion of intent, of religion in modernity expressed by way of constructing. This was a city designed for the car age however with a pedestrianised centre and a station half an hour from London. What do we would like cities to be now? These twee photos of Edwardian-style streets recommend a sure timidity.

Simply as essential as how they give the impression of being is how they work and the way they’re financed. One financial software used to nice impact after the second world struggle — and is being thought of once more — is land worth seize. The change in designation of land from agricultural to residential use may result (in accordance with a latest report by the Centre for Progressive Coverage) in an uplift of round 275 instances the unique worth. Land hypothesis within the UK has had a crushing impact on new growth, with landowners sitting on land till its worth soars by way of change of use.

For the postwar wave of latest cities, land was compulsorily bought at its agricultural worth — not together with what is called “hope worth”, the expectation of uplift created by the proposals. The cities had been then in a position to make use of that improve within the worth of their holdings and reinvest locally. Authorities assumed the danger and communities reaped the rewards. This methodology has light away within the UK, but the Dutch new city of Almere (usually dismissed as uninteresting however which I believe is totally fascinating) managed to seize an astonishing 90 per cent of the uplift in worth of its land for public infrastructure.

The imaginative and prescient of an enhanced group with the personal home and backyard at its centre additionally characterised earlier variations of the brand new city. Stevenage is sandwiched between Letchworth and Welwyn, two experiments in that much-studied English phenomenon, the backyard metropolis. The addition of the phrase “backyard” has generally been used to appease objectors, as if sounding somewhat greener will assuage neighbours’ fears concerning the horrors of urbanity. The time period is the invention of Ebenezer Howard, who wrote the quick however enduringly influential Backyard Cities of To-morrow (1898) — a guide that emerged exactly from a concern of London as a visitors and smoke-choked hellhole.

Backyard cities had been to be restricted in scale, surrounded by inviolable inexperienced belts; to be walkable, related by public transport; and to include all the weather required for a productive and civilised life: factories but additionally theatres and social golf equipment, market gardens, again gardens and even forests. They employed Group Land Trusts (non-profit companies that held the land on behalf of the group whereas additionally appearing as long-term stewards of public house) to maintain management and keep a stake in future success. They had been gently ridiculed on the time as priggish locations of self-consciously Arts and Crafts cottages, socialist sandals and skittles, cities with no pub. Letchworth’s important trade was a corset manufacturing facility and it boasted the world’s first visitors roundabout (1904).

Cities thrive on unpredictability, tradition, commerce but additionally a pinch of vice — a cocktail that’s tough to plan for

However the concept proved astonishingly influential. It unfold to Australia (Canberra was deliberate as a backyard metropolis), Singapore, Zelenograd close to Moscow (Lenin was rumoured to have visited Letchworth), the US (Augusta, Georgia, Reston, Virginia and the New Deal Greenbelt communities), to Christchurch in New Zealand and Jardim América in São Paulo.

If British backyard cities are sometimes mocked for his or her light suburbanity, you may also level to Milton Keynes, as soon as derided because the zenith of late fashionable dullness however now a thriving metropolis of greater than 280,000 with an eccentric mixture of structure, panorama (influenced by prehistory and Stonehenge as a lot as by Los Angeles), “car-centricity” in addition to walkability.

The arrogance sooner or later that spawned Milton Keynes within the late Nineteen Sixties has light. As prime minister, Gordon Brown tried to launch a brand new era of latest cities in 2007 and, to generate extra enthusiasm, christened them “eco-towns”. David Cameron’s coalition authorities jumped on the backyard metropolis bandwagon and tried to construct one at Ebbsfleet in Kent, although it nonetheless it seems suspiciously like some other property of govt properties. It stays, nonetheless, one of the crucial promising websites for a significant new city with its connections to high-speed rail and the capital. Then chancellor George Osborne subsequently downgraded his ambitions to the painfully quaint notion of “backyard villages”.

Constructing by decree is never easy. Take Palmanova, a garrison city established in 1593 by the Venetian Republic and meant as a mannequin metropolis. There are rumours that Leonardo da Vinci was concerned and, even when he wasn’t, its type was definitely influenced by his designs, deliberate in a star form for optimum artillery defence. It was a catastrophe. Nobody needed to dwell there. The local weather was unsuitable, the situation uninteresting, metropolitan life absent. Ultimately the authorities resorted to populating it with convicts who had been gifted free properties in a determined try to preserve it alive. It’s nonetheless a soporific rarity, an unattractive Renaissance city.

Cities thrive on unpredictability, tradition and commerce but additionally a pinch of vice. That cocktail is tough to plan for and utopian regulation usually kills it. Whereas generally pretty, ideally suited settlements based by well-meaning industrialists (Titus Salt’s Saltaire, Cadbury’s Bournville or Czech shoemaker Bata’s Zlín) are tainted by worker-capture; the identical concept as giving tech staff free snacks to maintain them on campus.

2.8mnResidents presently housed within the UK’s postwar new cities

Then there’s Poundbury, Britain’s personal retro-royalist utopia — a future that appears like a feudal previous, solely with parking garages and a department of Waitrose. Constructed on land outdoors Dorchester belonging to the Duchy of Cornwall, this new city/extension was in-built a vernacular fashion with a contact of classical, somewhat Georgian and a sort-of-medieval picturesque avenue plan. It’s undeniably well-liked.

In the meantime, our confidence sooner or later appears to have been hijacked by Large Tech billionaires with their missions to Mars and Moon-shots. For some time, “good cities” gave the impression to be the longer term however these started to sound suspiciously like data-mining operations.

If now we have misplaced that religion sooner or later that characterised Stevenage, and the power to construct the mandatory massive infrastructure (see the sorry HS2 high-speed rail saga), what’s left is to broaden current profitable cities. That is the place the “grey-belt” reappears, the easing of the city corset. However there are issues in even agreeing to what a metropolis (or a metropolis extension) of the longer term may appear to be.

The latest extraordinary response of the political proper, in each the US and the UK, to the thought of “15-minute cities” — spinning the notion of a walkable, dense and well-distributed conurbation right into a conspiracy concept about state management limiting residents’ entry to neighbourhoods of their automobiles — hints at these issues. Urbanists need compact quartiers, Paris-style, with native bakeries and surgical procedures; many homebuyers need double garages, driveways and massive gardens. And the massive builders that function one thing near a cartel within the UK market (their affect is exclusive in Europe and the outcomes have been dire) like these higher too — simpler to construct, and no issues with pesky infrastructure.

Maybe to counter the pervasive presence and affect of the housebuilders, there may additionally be house to accommodate self-builders and eccentrics, locations designated for experiments in new methods of communal residing, new types of possession, new sorts of structure. The rhetoric for the time being leans in direction of design codes and management, which is okay. But when the federal government is revising planning regulation, it might revisit guidelines facilitating residents to construct their very own extra particular person properties, suited to their explicit wants. Almere allowed residents to design their properties any manner they need, with no aesthetic controls. The outcomes are often weird however additionally they accommodate eccentricity and individuality. Are these not a vital ingredient of the English sense of id?

The postwar British new cities now home 2.8mn individuals and had been, on reflection, an audacious and unimaginable success. If there’s a lesson to be drawn from them, it is perhaps that authorities must take a central position. This isn’t one thing that may be left solely to a non-public sector that calls for short-term revenue. There may be additionally a possibility to revisit the commodification of housing that has led to the disaster. There are different types of tenure past residence possession.

Cities take time to construct. If there are just a few errors alongside the way in which, they are often rectified sooner or later. And we are able to take coronary heart in a single factor: this has been finished earlier than.

Edwin Heathcote is the FT’s structure critic

Discover out about our newest tales first — observe FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life & Art wherever you pay attention