Medieval peasants labored solely round 150 days per yr, a results of the church scheduling frequent holidays to maintain the labor power pleased.

Many mainstream financial historians do consider the common variety of working days for peasant laborers in England hovered round, and even generally beneath, 150 days per yr for sure stretches of the medieval interval, significantly the many years following the Black Demise.

Nonetheless, different economists and financial historians consider medieval laborers had a considerably longer working yr, averaging round 250 or extra days. Both means, financial historians usually don’t consider spiritual authorities had important management over the whole variety of days per yr peasants labored. As an alternative, financial historians usually consider the variety of days labored a yr was decided by a combination of things together with the quantity of wage-based work out there and laborers’ personal want to work.

For years, the declare that medieval peasants labored solely round 150 days a yr has circulated on-line. The declare has taken a wide range of varieties, amongst them a number of memes that juxtaposed the declare with work showing peasants toiling within the fields.

(Instagram account @classicaldamn)

Of those memes, the one which seems to have circulated most generally consists of textual content positioned above and beneath a element of a miniature from the “Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry,” a Fifteenth-century illuminated manuscript from France. The textual content reads:

Medieval peasants labored solely about 150 days in a yr. The Church believed it was necessary to maintain them proud of frequent, necessary holidays. You may have much less holidays than a Medieval peasant.

The meme seems to have originated from a Might 15, 2022, Instagram post by historic meme account Classical Rattling (Snopes has reached out to Classical Rattling to verify their authorship of the meme, and can replace this story if we hear again). As of this writing, that put up had obtained round 15,000 likes.

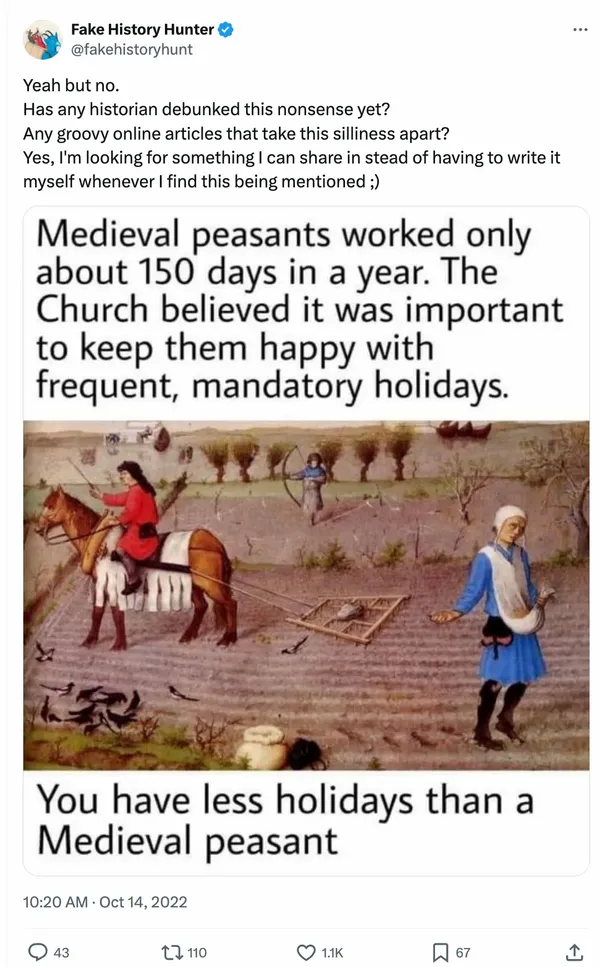

Was the declare made within the meme, that medieval peasants labored solely 150 days a yr due to frequent and necessary church holidays, right? Some in style social media posts have known as the declare nonsense. For instance, a Might 2022 post within the r/badhistory subreddit known as it “weird,” “unreasonable,” and “ahistorical.”

Equally, an October 2022 thread by the favored X account Pretend Historical past Hunter opened by pairing the meme with the caption:

Yeah however no.

Has any historian debunked this nonsense but?

Any groovy on-line articles that take this silliness aside?

Sure, I am searching for one thing I can share in stead of getting to put in writing it myself every time I discover this being talked about 😉

(X person @fakehistoryhunt)

Regardless of these assertions that the meme is nonsense, its circulation — together with the engagement it provoked — solely elevated over time. For instance, a Might 21, 2024, Instagram post that featured the meme in entrance of an animated background displaying rose petals falling round columns obtained greater than 388,000 likes, greater than 25 instances the quantity obtained by Classical Rattling’s authentic put up.

The meme’s persistence within the face of the assured dismissiveness of social media customers claiming to debunk it has, understandably, left many web customers unsure whom to consider.

In July 2022, for instance, a Reddit person made a post to the r/AskHistorians subreddit describing the meme and asking: “Is it true that medieval peasants labored solely 150 days in a yr as a result of Church ensuring that they had frequent necessary holidays?” In April 2023, a distinct person asked the identical subreddit: “How correct is that this, and the way would these ‘holidays’ truly be spent?”

Related questions have additionally been requested on Quora and on Stack Change’s Historical past board. For years, Snopes has additionally obtained quite a few requests from readers asking us to look into the query.

In an try to offer a definitive verdict on the veracity of the declare that medieval peasants labored round 150 days a yr, Snopes spoke with a number of students together with Gregory Clark, the economist most often credited with originating the 150-day-a-year estimate, and Juliet Schor, the economist who first popularized the declare in her 1991 e book “The Overworked American.”

We additionally spoke with Jane Humphries and Jacob Weisdorf, two financial historians who at the moment research the query of the size of the medieval working yr and have lately printed work supporting a 150-day estimate, at the very least for sure many years in medieval England.

Along with talking to those students, Snopes additionally carried out intensive analysis into the net lifetime of the declare to be able to decide when it first started to unfold on-line and the way it has modified over time. We moreover examined quite a few in style debunkings of the declare, with particular consideration to the proof cited as proof towards the declare.

Finally, we discovered that the declare that medieval peasants labored round 150 days a yr remains to be largely accepted as a sound estimate by tutorial financial historians, at the very least in England for a interval beginning round 1350 and lasting between just a few many years and greater than a century, relying on the methodology used to review the information.

A caveat applies to the second a part of the declare made within the meme, specifically that the variety of days medieval peasants labored was the direct results of a lot of necessary Christian holidays. This was one thing no financial historian Snopes spoke to thought of a big consider any estimate of the medieval working yr.

Snopes additionally discovered that in style makes an attempt to debunk the declare incorrectly introduced the declare as outdated or not grounded in proof, an estimate of round 150 days per yr of labor is, actually, at the moment accepted by many mainstream financial historians who research medieval England, which is the a part of Europe that has obtained by far probably the most consideration from English-speaking financial historians within the size of the medieval working yr.

As a result of the declare that medieval peasants labored 150 days as a result of frequency of non secular holidays comprises info that’s each true and false — at the very least in line with many mainstream financial historians — Snopes charges it as a “Combination” of right and incorrect info.

The 150-Day Estimate: What Consultants Say

As Atlantic journal author Amanda Mull defined in a prolonged 2022 article about on-line curiosity in medieval working patterns, the declare that medieval peasants labored 150 days a yr entered the general public consciousness because of a bestselling 1991 e book by Schor, an economist and sociologist at the moment primarily based at Boston Faculty.

That book, titled “The Overworked American: The Surprising Decline of Leisure,” was a rebuttal of claims made within the Nineteen Thirties and Nineteen Forties that capitalism would ultimately lead to shorter working hours, elevated leisure time and improved requirements of residing for People. As an alternative, Schor argued, financial development and residing requirements each stagnated within the Nineteen Seventies, after which People turned caught in an “insidious cycle of work-and-spend.”

Within the third chapter of the e book, Schor emphasised what she noticed because the comparatively current nature of demanding and unrewarding work schedules by compiling pre-existing estimates of the size of the working yr from earlier durations in historical past, starting with the thirteenth century.

Schor’s alternative to start out with the thirteenth century was not arbitrary. It was, actually, throughout this century that cracks started to emerge in England’s system of unfree peasant labor, by which many peasants had been tied to a lord’s land and had been required to carry out a certain quantity of unpaid labor on the lord’s behalf annually.

In a course of that sped up considerably through the 14th century — notably throughout and after the Black Demise, which reached England in 1348 — English peasants more and more paid their landlords not with labor however with cash, which they earned via wage-based work. In consequence, accounts of day by day and annual wages began appearing in larger numbers within the historic file.

Regardless of the emergence of accelerating quantities of wage information beginning across the thirteenth century, the proof for this era was nonetheless nowhere close to as sturdy or dependable as the information usually utilized by fashionable economists.

Particularly, estimates that place the medieval working yr at round 150 days have largely been primarily based on manorial information, which had been nowhere close to as complete as fashionable accounting paperwork. As Humphries and Weisdorf, the financial historians, instructed Snopes in a collectively written electronic mail:

The core drawback is that, whereas there are fragmentary information, there isn’t a dependable systematic proof on the variety of days labored traditionally in any of our archival sources. Or, if such proof does exist, now we have not but been capable of uncover it!

In different phrases, students trying to review the medieval financial system are lacking a important piece of the puzzle, specifically the variety of days within the common medieval working yr. With out that info, the medieval English financial system as a complete can’t be totally understood.

For the thirteenth century, Schor cited an estimate of 150 days of labor a yr per household, or 135 12-hour days per grownup male. The estimate had been proposed in a 1986 paper written — however by no means formally printed — by Clark, an economist who had accomplished his Ph.D. at Harvard College the earlier yr. In an electronic mail to Snopes, Clark, now a distinguished professor emeritus on the College of California, Davis, mentioned he arrived at this quantity by evaluating information of annual and day laborers.

Clark mentioned he not agreed with the methodology used to calculate the estimate attributed to him in Schor’s e book, however had since come to assist a considerably greater estimate. In a paper printed within the Financial Historical past Evaluate in 2018, Clark expressed assist for an estimate nearer to 300 days a yr, representing a working yr just like these recorded within the nineteenth century.

Clark described his present methodology as being primarily based on residing requirements. One of many courses of proof he has used as a proxy for residing requirements is the quantity spent on provides required to feed employees whereas they had been on the job, as recorded in medieval employers’ accounts.

If medieval employees labored solely 150 days per yr in sure durations, in line with Clark, then the relative quantity employers spent on rations throughout these durations must be roughly half what was spent throughout later durations on employees who, because of enhancements in record-keeping, are securely identified to have labored 300 days a yr on common.

As an alternative, Clark identified, the connection between the quantity spent on employees’ meals and the quantity spent on their day by day wages remained surprisingly steady from 1350 to 1869, one thing Clark has taken as robust proof that employees in medieval England on common labored roughly the identical variety of days per yr as employees within the nineteenth century.

Though Clark has modified his thoughts concerning the 150-day estimate since he first instructed it in 1986, quite a few different well-known financial historians engaged on the identical questions have lately endorsed it, or estimates near it, for important durations of time in medieval England.

Two such financial historians are Humphries, a retired professor of financial historical past at All Souls Faculty, Oxford, and Weisdorf, a professor of financial historical past at Rome’s Sapienza College. In 2019, they co-wrote an article, printed within the Financial Journal, that focuses on laborers who had been paid wages yearly, reasonably than day by day. Annual employees, they instructed Snopes in a collectively written electronic mail, represented round 40% of the labor power.

Though the working yr of day laborers was not the first focus of the article, Humphries and Weisdorf included a chart displaying the variety of days per yr a day laborer would have wanted to work on common to be able to earn the identical revenue as a laborer who obtained an annual wage.

In response to Humphries and Weisdorf’s calculations, that quantity fluctuated considerably over the course of the medieval and early fashionable durations, however between round 1325 and 1350 it plummeted from a peak of barely greater than 200 days a yr to simply above 100 days a yr — far beneath the 150-day declare. This drop has usually been attributed to the Black Demise, which killed an estimated 30% to 45% of the English inhabitants between 1348 and 1350 and drastically reshaped England’s labor market.

Whereas the variety of days required for a day laborer to earn the identical yearly revenue as an annual laborer started rising round 1375, in line with Humphries and Weisdorf’s calculations, it did so slowly, and stayed beneath 150 days a yr till round 1525.

Humphries and Clark are usually not outliers within the discipline of financial historical past. Among the many different financial historians who’ve supported the 150-day estimate, or estimates near it, are Stephen Broadberry, Bruce M.S. Campbell, Alexander Klein, Mark Overton and Bas van Leeuwen, the coauthors of “British Financial Progress: 1270–1870,” a survey of financial historical past published in 2015 by Cambridge College Press.

A review of the e book, printed the next yr within the Journal of Financial Historical past, famous that a few of the authors’ decisions would possibly show controversial however predicted that it was “more likely to be a reference and textual content for college kids of this historical past for the following a number of many years.”

Within the e book’s eighth chapter, the authors mentioned estimates of the lengths of medieval and later working years primarily based on subsistence baskets, a time period the authors outlined because the sum of money required at a selected cut-off date to be able to afford fundamental residing bills, which had been decided utilizing historic value information.

Utilizing this technique, the authors established their estimates by calculating the variety of days a laborer would wish to work to afford the price of the subsistence basket in a selected yr. For instance, on Web page 312, they wrote:

In 1290, when an unskilled agricultural labourer earned round 1 and a half pence a day, a farmhand would wish to have labored for 150–160 days to be able to afford the respectability basket of ale, bread, beans and peas, meat, eggs, butter, cheese, cleaning soap, fabric, candles, lamp oil, gas and hire.

The authors continued on to say that, in line with these calculations, a 150-day workyear most likely wouldn’t have been sustainable for a sole breadwinner who wanted to assist a household of 4 in 1290, however in addition they famous: “For a single man that was a sensible risk.”

Of their correspondence with Snopes, Clark, Humphries and Weisdorf all emphasised that, for economists and financial historians, the query of what number of days per yr medieval peasants labored stays an open debate.

“It might be pure for us to level to our personal estimates because the extra dependable ones,” Humphries and Weisdorf instructed us, “however we consider all the present numbers are legitimate in their very own proper.”

One other issue all three financial historians agreed on was that it’s unlikely the calendar of Christian holidays had a lot impact on the truth of the medieval working yr.

For Clark, who now helps a excessive estimate in line with which medieval English laborers labored as a lot or greater than fashionable American employees, the maths for that a part of the declare merely does not work. Even when employees did solely work 150 days a yr he instructed us, “it doubtless didn’t stem from Church prohibitions of labor on Saints’ Days.”

Equally, Humphries and Weisdorf described this a part of the declare as a “moot query,” explaining:

We all know that there have been many instances when proscription towards work was ignored, as to be anticipated when a lot agricultural labour was relentlessly steady (feeding animals, milking, herding, and many others.) … Utilizing spiritual and later political holidays as a information to working time is like utilizing recommendation books as a information to behavior, indicative maybe however not decisive.

Relatively than spiritual holidays, the elements financial historians who research this era are inclined to view as the explanation why peasants didn’t work for important durations of the yr embody the supply of wage-based work, wage charges, and even, merely, their very own want to work.

In sum, the economists and financial historians who’ve carried out analysis into the size of the medieval English working yr are nicely conscious of the restrictions of their proof, together with the issue of unpaid labor. These students nonetheless consider this can be a query price finding out utilizing the proof out there, nevertheless, as a result of understanding the common variety of days laborers labored per yr is a important element of understanding the medieval financial system as a complete.

On account of the problem of quantifying the medieval working yr, a big quantity of the work of financial historians within the interval consists of proposing and evaluating completely different strategies for estimating how a lot medieval laborers labored.

These strategies, which depend on several types of proof, have resulted in numerous estimates which have discovered various levels of acceptance amongst financial historians as a complete. Amongst these estimates, the 150-days-a-year one has — at the very least for sure durations in England — been backed up by a number of several types of proof, and it continues to have many skilled supporters.

The 150-Day Estimate on the Web

In a telephone dialog, Schor instructed Snopes that when she printed “The Overworked American” in 1991, she had some expectation that readers is likely to be within the part on the medieval working yr. Nonetheless, she mentioned, the quantity of curiosity within the 150-day declare that she’s seen on-line in recent times has taken her unexpectedly. “It simply popped up at random instances,” she mentioned.

The web lifetime of the declare seems to have begun in earnest in August 2013, with the publication by Reuters of an op-ed written by Lynn Parramore, a author and senior analysis analyst on the Institute for New Financial Historical past.

That op-ed, titled “Why a Medieval Peasant Received Extra Trip Time Than You,” launched Schor’s work to a brand new, broader viewers, updating it at factors with more moderen information. The passage most related to the declare investigated right here learn:

The Church, conscious of how one can maintain a inhabitants from rebelling, enforced frequent necessary holidays. Weddings, wakes and births would possibly imply every week off quaffing ale to have fun, and when wandering jugglers or sporting occasions got here to city, the peasant anticipated day off for leisure. There have been labor-free Sundays, and when the plowing and harvesting seasons had been over, the peasant bought time to relaxation, too. Actually, economist Juliet Shor [sic] discovered that in durations of significantly excessive wages, similar to 14th-century England, peasants would possibly put in not more than 150 days a yr.

On this excerpt, Parramore caught near Schor’s authentic framing, significantly relating to the function of the church. Notably, each authors talked about the statement of frequent spiritual holidays as one in every of some ways — not the one means — medieval peasants might need spent their time outdoors of labor.

Parramore’s digestible presentation of Schor’s work didn’t instantly lead to memes concerning the 150-day declare, but it surely did provoke the earliest instance of an try and debunk the 150-day declare addressed to a large viewers that Snopes has been capable of determine.

Printed in September 2013, this debunking took the type of a blog post on the web site of the Adam Smith Institute, a British suppose tank and lobbying group that usually helps pro-capitalist and anti-regulation insurance policies. That weblog put up, which is unsigned, started:

One of many issues that irks my choler, yanks my goat for those who like, is this concept that the medieval peasant led a lifetime of unimaginable leisure, needed to work vastly lower than we poor saps floor down below capitalism need to. It is solely nonsense in fact.

Over the course of the transient put up, the creator pointed to the existence of unpaid work, each unfree labor achieved for a lord and duties that is likely to be thought of chores, similar to feeding livestock or cooking.

The creator ended on a political be aware, claiming that Schor’s analysis, then 22 years outdated, was being “trotted out” in an try and shore up assist for laws guaranteeing paid trip days for American employees, one thing that had been discussed in Congress earlier that yr.

Though some feedback left on the Adam Smith Institute weblog put up agreed with its creator’s analysis of Schor’s work as introduced by Parramore, others defended the 150-day declare, citing inaccuracies within the put up’s claims about medieval historical past and characterizations of Schor’s scholarship (the put up doesn’t point out Clark). “It is a reasonably dishonest and shameful piece,” one commenter wrote in 2015.

Whatever the debunking posted on the Adam Smith Institute weblog, Parramore’s op-ed about Schor’s work continued to unfold on-line. In November 2016, Parramore’s piece was republished by the economics weblog Evonomics and written about by a columnist at Inc. Additionally in November 2016, Schor’s analysis was summarized within the Day by day Mail.

The following main improvement within the on-line historical past of the 150-day declare occurred in April 2022, when Azie Dungey, a tv author, made an X put up that learn:

Medieval peasants labored solely about 150 days out of the yr. The Church believed it was necessary to maintain them proud of frequent, necessary holidays.

You may have much less free time than a Medieval peasant.

Snopes has, up to now, been unsuccessful in reaching Dungey for remark about the place she first encountered the declare, however in a follow-up put up she linked to a 2021 Medium post that introduced Schor’s analysis, largely following Parramore’s 2013 op-ed.

Dungey’s put up, which on the time of this writing had obtained round 20,000 reposts and 114,000 likes, represented the declare’s first actual social-media second. Inside a month, Dungey’s put up was coated by The Atlantic and have become the topic of a second debunking, this time posted by a Redditor to the r/badhistory subreddit.

Though this debunking went into extra element concerning the historical past of the 150-day declare than the Adam Smith Institute weblog put up, accurately tracing the estimate from Schor again to Clark, it didn’t point out the analysis a number of completely different financial historians had printed supporting the 150-day declare within the many years since Schor’s e book first appeared. In different phrases, the put up introduced the estimate as out-of-date and fringe, regardless of the variety of mainstream financial historians who at the moment assist it.

Just like the Adam Smith Institute weblog put up, the r/badhistory debunker’s put up targeted on what they noticed because the 150-day estimate’s lack of lodging for unpaid work achieved for a lord. They didn’t, nevertheless, point out the affect of the Black Demise on the English labor market, which led to a drastic discount of labor-based obligations amongst English peasants on the similar time the common working yr dropped from round 200 days to beneath 150 days — at the very least in line with Humphries and Weisdorf’s calculations.

The r/badhistory debunking additionally identified that the 150-day estimate doesn’t account for time spent doing chores similar to cooking or feeding livestock. That is true, however the debunker didn’t be aware that greater estimates just like the one endorsed by Clark, by which medieval peasants labored as many as 300 days a yr on common, additionally don’t account for these duties. In different phrases, on this level the debunker’s grievance was not correctly concerning the 150-day declare, however as a substitute concerning the sorts of actions economists and financial historians think about work, one thing that for the medieval interval is essentially dictated by the restraints of the quantifiable historic proof.

Two days after the r/badhistory debunking was posted, the Instagram account Classical Rattling posted the meme talked about firstly of this story. Notably, the phrases utilized in that meme virtually precisely matched Dungey’s put up, together with the “frequent, necessary holidays” phrase that originated with Parramore’s paraphrase of Schor’s analysis.

The Medieval Peasants Meme in Context

The declare that medieval peasants labored, on common, round 150 days a yr has a historical past that may be traced again to 1986, when Gregory Clark first proposed it. Over the next many years it was launched to more and more broader audiences via a sequence of citations and paraphrases.

Of those introductions, 4 had been noteworthy: first, Schor’s quotation of Clark in 1991’s “The Overworked American”; second, Parramore’s abstract of Schor’s work in a 2013 op-ed; third, Dungey’s 2022 X put up; and fourth, the Instagram account Classical Rattling’s posting of a meme primarily based on Dungey’s X put up, additionally in 2022.

As public consciousness of the declare elevated, so too did makes an attempt to debunk it via posts on X, Reddit and numerous blogs. Nonetheless, regardless of what a few of these makes an attempt to debunk the declare have asserted, Clark’s unpublished 1986 paper shouldn’t be at the moment the one tutorial supply for the 150-day estimate.

As an alternative, primarily based on more moderen scholarship, many — although not all — tutorial economists and financial historians have come to simply accept the 150-day estimate, at the very least for England throughout a lot of the 14th century, and generally even later.

In a telephone dialog with Snopes, Parramore mentioned that, in her opinion, the broadening of scholarly assist for the 150-day estimate might be at the very least partly attributed to adjustments in how teachers perceive the function of historical past in economics. Particularly, she cited the expansion of curiosity amongst economists in contemplating historic information from pre-modern durations, versus the purely mathematical fashions that dominated the sector for a lot of the twentieth century.

“One of many issues with economics as a self-discipline because the Nineteen Fifties has been an absence of consideration to historical past,” Parramore mentioned. “It is solely been lately, actually, that financial historical past has come again into the image.”

On the similar time, she mentioned, on-line curiosity within the 150-day estimate doubtless displays in style dissatisfaction with the realities of the fashionable Western financial system, a lot alongside the strains of what Schor described in 1991. In response to Parramore, that dissatisfaction worsened dramatically throughout and after the COVID-19 pandemic, which she described as “a very traumatic expertise for the labor power.”

Whether or not introduced within the type of scholarly literature or on-line memes, Parramore mentioned, the declare that medieval peasants labored round 150 days a yr “strikes a nerve as a result of folks really feel overworked, and this provides them a historic perspective. They’re trying again in time and considering, did all people work this difficult for thus little?”

Finally, the declare that medieval peasants labored 150 days as a result of frequency of non secular holidays comprises info that’s each true and false — at the very least in line with many mainstream financial historians. As such, Snopes charges it as a “Combination” of right and incorrect info.