Rust Belt Reporter: A Memoir

John Gallagher

200 pages; Wayne State College Press

$26.99

As a journalist in Detroit for greater than three a long time, John Gallagher labored the entrance strains of double crises: the hollowing out of a fantastic American metropolis and the collapse of the newspaper enterprise mannequin required to inform that story.

The town’s shrinkage is mirrored within the exodus of its individuals, the inhabitants plummeting from greater than 1.8 million in 1950 to fewer than 700,000 at the moment.

Addressing what he characterizes as “the dual calamities besetting town and journalism,” Gallagher says the mix “molded a public picture of Detroit as a spot on the finish of the road with abandon-hope-all-ye-who-enter-here posted on the metropolis’s borders, and with its journalists struggling one hammer blow after one other.”

However all shouldn’t be misplaced. In Rust Belt Reporter, the writer particulars his personal “principle of city restoration.” (Extra on that in a bit.)

Gallagher’s expertise is rooted in city affairs versus media economics, and he makes no declare to a parallel “principle of journalism restoration.”

However his reporting appeared in a newspaper, the Detroit Free Press, that has managed to pump out good work over the previous 4 a long time regardless of the cascading woes of a contentious joint working settlement, an extended and bitter strike, a jolting possession change and the income pressures plaguing information organizations all over the place.

(Photograph/Nic Antaya)

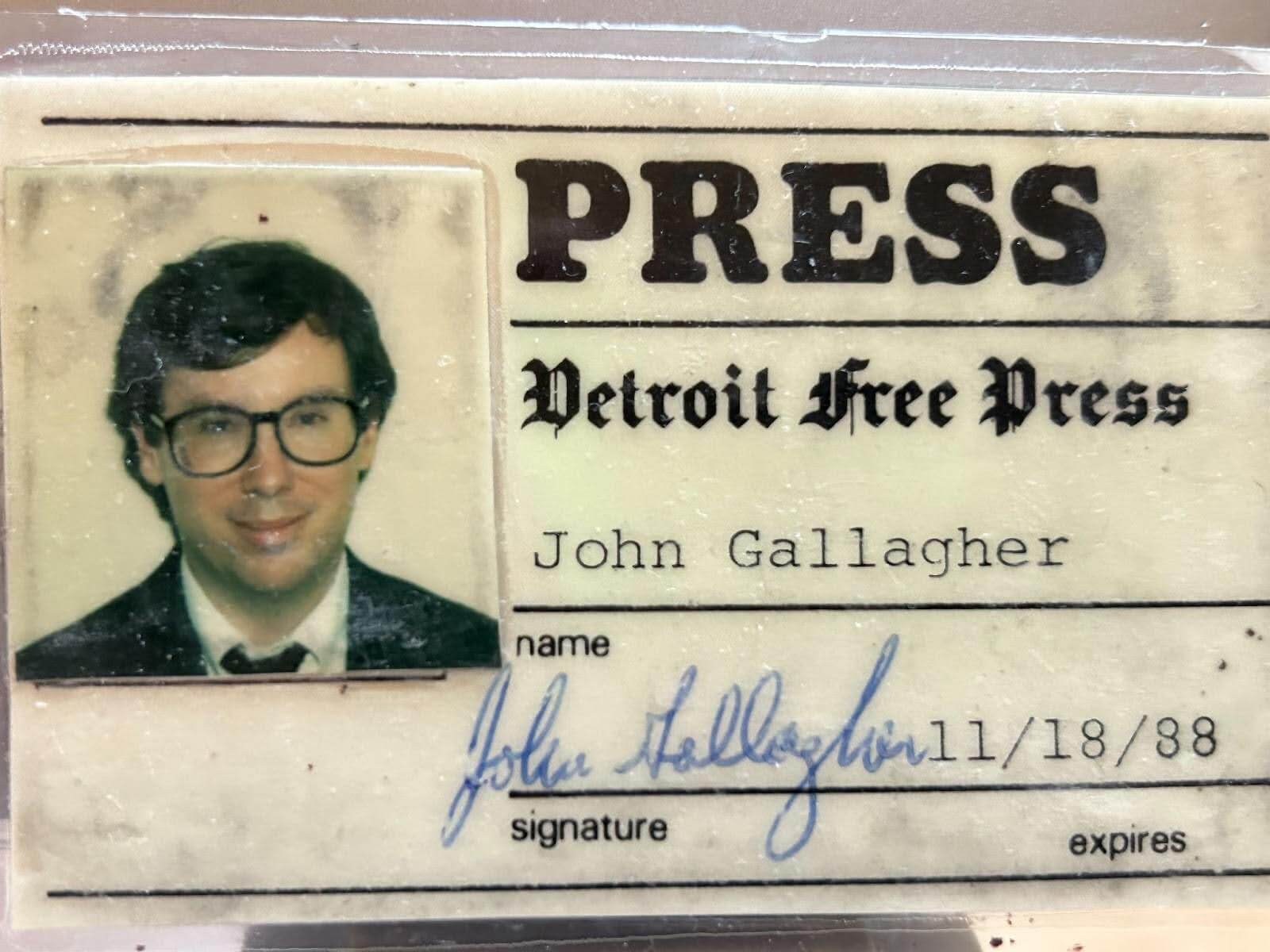

Gallagher, who retired as a columnist for the enterprise part in 2019 after 32 years with the paper, digs into his personal story as an old-school newsman adapting to the digital world.

(I labored for the Free Press for practically 20 years, overlapping with Gallagher for 5, and have been gone for greater than 30.)

Gallagher obtained his begin a half-century in the past, on the legendary Metropolis Information Bureau in Chicago. That put his resume in good firm. Amongst different CNB alums: Mike Royko, Sy Hersh and Kurt Vonnegut.

Though he obtained no formal coaching there, he credit Metropolis Information with educating him the basics, a few of them helpful all through his profession (writing quick) others much less so (punching a narrative onto a ticker tape with none approach of seeing what he was typing).

As a wire service offering copy for numerous Chicago media, CNB deployed a crew of low-paid rookies to all the massive tales on the town. That put Gallagher on the scene with such figures as Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal and, in fact, the legendary boss of Chicago politics, Mayor Richard J. Daley.

He describes a quick dialog with Vice President Nelson Rockefeller — within the days earlier than Secret Service safety would make such an impromptu encounter unthinkable — as “a type of events that illustrate one of many chief perks of a journalist’s life: you get to see, take heed to, and meet fascinating individuals on a regular basis.”

These have been the times when Royko, the king of native journalism, held court docket most nights after deadline on the Billy Goat Tavern, a saloon submerged beneath Michigan Avenue not removed from town’s largest newspapers.

John Gallagher’s press move from the Detroit Free Press. (Courtesy)

At first, Gallagher says he “knew Mike Royko the best way any Chicagoan did, as an avid reader of his columns within the Every day Information and, in a while, within the Solar-Occasions and Tribune.”

That modified some over time, largely as a dividend of time Gallagher invested at The Goat. At one level he discovered himself amongst 20 candidates for the job of Royko’s legman.

He didn’t get the job, certainly one of a number of recollections Gallagher recounts of issues not figuring out. Describing an expertise that the majority of us can relate to, he writes a chapter headed: “On By no means Profitable a Pulitzer.”

Shifting on from Chicago in 1978, Gallagher joined the Democrat & Chronicle in Rochester, New York, dwelling of Eastman Kodak. The corporate invented the primary digital digital camera in 1975 however feared cannibalizing its movie enterprise and ended up swamped within the wake of digital. Struggling a destiny acquainted to journalists all over the place, Kodak’s workforce shrunk from 60,000 to just some thousand.

Gallagher’s time in Rochester additionally offered him with a style of Rust Belt decline, town’s inhabitants having declined from 300,000 in 1950 to 250,000 some three a long time later.

It wasn’t till his subsequent job, at The Submit-Commonplace in Syracuse, New York, that Gallagher discovered his footing as a journalist.

In a state of affairs that many readers may recall from early days on the job, one of many editors saddled Gallagher with an project he’d been pitching to the employees with no takers.

In no place to duck it, Gallagher produced a telling story about neighborhood gentrification.

“My editor was delighted,” Gallagher recollects. “He advised everybody he had tried for weeks to curiosity his reporters within the story till the brand new man confirmed up and did it in a day.” He provides:

After my years of disappointment on the Rochester paper, this had gone so simply for me that I skilled a brand new feeling. It was a realization that, sure, I can do that job. … The boldness I gained did as a lot as something to hold me by way of all of the years of journalism that adopted.

Like lots of journalists of their 30s, Gallagher obtained stressed. After a number of years in Syracuse, he secured a fellowship — the Bagehot Fellowship in Economics and Business Journalism at Columbia College — as his subsequent step.

His favourite seminar through the fellowship featured New Yorker author Ken Auletta describing his back-and-forth a few single phrase with famend editor, William Shawn. Within the course of, Gallagher discovered one thing about phrase alternative that guided the best way he wrote from that time ahead.

Gallagher returned to Syracuse for just a few months after his fellowship however quickly obtained a name from Free Press enterprise editor Tom Walsh, who had contacted the Bagehot workplace searching for a brand new reporter.

Gallagher’s time in Detroit coincided with arduous instances for each the newspaper and town.

Knight Ridder and Gannett, homeowners of the Free Press and The Detroit Information, kicked off years of controversy in 1986 after they declared a joint working settlement that wasn’t lastly authorized till 1989 with a 4-4 vote of the U.S. Supreme Court docket.

In July 1995, unions on the Free Press and The Detroit Information went on strike somewhat than settle for a administration plan that may have, amongst different issues, eradicated contractual raises in favor of pay hikes granted strictly on the idea of advantage.

The unions’ most up-to-date work stoppage had occurred 15 years earlier, simply because the 1980 Republican Nationwide Conference was getting underway within the metropolis. However that strike lasted solely per week, and Gallagher stories that many staffers have been anticipating a strike of comparable period.

It didn’t work out that approach. The 1995 strike lasted for 19 months, disrupting the lives and careers of a whole bunch of staffers and without end diminishing the newspapers’ viability and affect.

A union activist who served three two-year phrases as president of the Newspaper Guild of Detroit, Gallagher writes:

1 / 4 century on, I see the strike as a catastrophe for the unions and a catastrophe for the businesses and a miscalculation on either side that hastened the decline of journalism in a serious American metropolis. Surveying the wreckage from this distance, I name the strike a double suicide by the businesses and the unions, a battle the place victory was indistinguishable from defeat.

The town’s twin crises have been addressed by Stephen Colbert when former Free Press editorial web page editor Stephen Henderson, a Pulitzer winner who wrote the foreword to Gallagher’s memoir, appeared on his Comedy Central present in 2013.

“You reside in Detroit and likewise work within the newspaper trade,” Colbert noticed. “Are you a glutton for punishment?”

As a lot as Gallagher describes issues going through town and the information enterprise as “twin calamities,” he doesn’t counsel frequent parentage.

He sums up the stats framing the plight of American newspapers like this:

- Newspaper advert income within the U.S. plummeting from $50 million in 2005 to lower than $10 billion within the early 2020s

- Newspaper circulation dropping from about 62 million in 1992 to lower than half that, for on-line in addition to print, in 2020

- Newsroom staffing falling from about 70,000 in 2004 to about 30,000 in 2020.

Henderson, himself a founding father of a brand new media startup, BridgeDetroit, contains in his foreword a sobering evaluation of journalism’s dwindling capability.

Asking whether or not the information sources at present deployed in Detroit might match the extent of protection dedicated to town’s crises a decade in the past, he concludes: “Anybody who has been paying consideration must say no.”

However he additionally expresses the hope that younger journalists ”may journey the identical arc that Gallagher so artfully illustrates on this memoir. A lifetime of story-telling, punctuated by progress, and studying, and affect, and pleasure.”

Gallagher affords no panaceas for journalism writ giant. However he exhibits how the information trade’s transformation can get began one journalist at a time. His profession suggestions for growing topic experience, writing books and interesting communities are all of the extra related and helpful amid the revolution in how the information is produced, delivered and absorbed.

As for town, Gallagher writes: “If I noticed in my every day reporting shoots of hope sprouting up across the metropolis, I used to be usually alone in my optimism.” By the use of instance, he mentions a 2009 cover story in Time (“The Tragedy of Detroit”) that listed three most important villains: “white racism, Coleman Younger and a delusional dependence on the auto trade’s perception in its personal virtues.”

Gallagher pushes again on the concept Younger, Detroit’s first black mayor (1974-1994), bears main duty for town’s decline. In a 2013 story headlined “How Detroit Went Broke,” Gallagher and a colleague reported that “Younger was the one Detroit mayor since 1950 to preside over a metropolis with extra revenue than debt …”

So the place ought to the blame be positioned? Like Time, Gallagher blames white racism, buttressing his personal reporting with such sources as “The Origins of the City Disaster: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit” by Thomas Sugrue.

Gallagher additionally endorses historian Lewis Mumford’s view, revealed in 1958, that lots of city decay should be pinned on the American “faith of the motorcar.” Gallagher is very important of Detroit space freeways that destroyed such metropolis neighborhoods as Black Backside, a vibrant Black group displaced by the Chrysler Freeway. Touted as a approach of enabling extra individuals to get into town, Gallagher argues that as an alternative they fueled the white exodus to the suburbs.

However how you can reverse that circulation of individuals? Gallagher stories that “many individuals date Detroit’s comeback to the day in 2010 when billionaire businessman Dan Gilbert moved his firm, Quicken Loans, from the suburbs to downtown Detroit.” Gilbert challenged different moguls to do likewise and inside just a few years he had purchased or leased 100 downtown properties, finally together with the constructing housing each the Free Press and The Detroit Information.

The writer describes his “principle of city restoration” as one “through which the normal sources of management — mayors, governors, the federal authorities — have been much less vital than a mosaic of efforts by non-public and nonprofit actors, lots of them working quietly within the distressed neighborhoods that had been deserted by car-crazy, suburb-bound America.”

A decade after town declared the biggest urban bankruptcy in American history, Gallagher notes: “In Detroit I might see new concepts of city restoration germinate, develop, bear fruit, and encourage restoration efforts all over the place.”

As a lot as guests to downtown lately marvel on the exercise and obvious prosperity, a cruise by way of lots of the metropolis’s nonetheless struggling neighborhoods reveals the unevenness of Detroit’s restoration.

Gallagher cites work he did with colleagues over time documenting the causes of neighborhood decline, particularly “banks and financial savings establishments (that) routinely underserved even middle-class Black neighborhoods in Detroit in comparison with the loans they made in white districts.”

He additionally highlights indicators of neighborhood rebirth, noting particularly the efforts of nonprofit teams and neighborhood activists to reclaim their streets.

“Detroit’s story is so various, with a lot conflicting proof of progress or lack of it, that even at the moment one can lean towards both optimism or despair,” Gallagher concludes.

”I select hope.”